Introduction

A challenge in exploring the relationships between librarians, library practices, and romance fiction is that there is no strong conceptual frame on which to base it. This study[i] finds the metaphor of the dalliance a useful one through which to explore these relationships. The seminal work of Pamela Regis in identifying the “eight essential elements” in the building of the romance fiction narrative provides the structure for exploring such a metaphor (30). In this study, these elements flesh out the metaphor, providing what Bourdieu would refer to as a “thinking tool” (Wacquant 50); in other words, Regis’s elements are used as a way to think about the relationship between librarians in public libraries and the romance fiction books in the collection. The metaphor permits an observation of how librarians, through their practices, enact a courtship with romance fiction books, but also how their relationship is seen to be a trifle—a frivolous, casual involvement that amounts to toying rather than one of commitment, and certainly not one that ends in betrothal. The metaphor is played out through an exploration of the physical shelving placement of romance fiction in public libraries and its representation on the library catalogue, which will be supported by the perceptions of romance fiction expressed by a number of librarian interviews.

The Society Defined

In coming to a definition of romance fiction, Pamela Regis identifies the “eight essential elements” that are required for a narrative trajectory that takes the central protagonists “from encumbered to free” (30). She identifies them as: the society in which the encounters take place, the meeting, the barrier to love, the attraction, the declaration of their intentions, the point of ritual death—the low point in the relationship, the recognition in being able to move the relationship forward, and finally, if at all possible, the betrothal and the essential inclusion of the happy ending, without which the genre of romance fiction is “rendered incomplete” (22). This paper will use these elements as the narrative trajectory for the report of this study. Regis draws upon the work of Northrop Frye to say that “the essence of romance is the ‘idealized world’ it embodies in its texts” (Regis 20; Frye Anatomy 367). Librarians present their libraries as democratic places providing social capital (Goulding 3). In a sense they are positioned as informational utopias aiming to provide their communities equal access to resources, including fictional reading. Here, libraries too are “idealized worlds” that are embodied through the texts they make available to their community and the services provided.

A literary experience can be found in every work of literature, even when it comes from a popular core (Frye Educated 265). This reflects the argument of this paper that all romance fiction is a literary experience. It is from this position that the assumptions of librarians, as cultural custodians who work with the “world of words” (Frye Educated 266), are examined by looking at their understanding of romance fiction. Fiction collections and provision of reading selections are core to public library services. There is significant evidence that romance fiction novels are included in library collections, however, this study goes beyond looking at the holdings of the state-wide library system of New South Wales and explores the shelf placement, the library catalogue records and their level of completeness, and the extent of staff engagement with romance fiction collections. For this to be achieved, interviews with librarians were conducted, and shelf classifications with their corresponding floor locations were examined through the enactment of physically entering libraries and examining the placement of romance fiction in relation to the rest of the fiction collections in the library.

Librarians Meet Romance Fiction

Public librarians pursue a rhetoric of developing collections that meet the reading interests of the broader community. Public libraries include romance fiction in their collections in a variety of ways, through purchases and through donations. Discussions on the need for romance fiction to be included into public library collections led to the need for romance fiction reviews in the library trade journals (Chelton 44) to assist in its selection. For instance, in May 1994, Library Journal, a widely read professional journal, introduced the first romance review column in the literature of practice. In 1987, the first bibliographic guide for readers’ advisory librarians, Kristin Ramsdell’s Happily Ever After: A Guide to Reading Interests in Romance Fiction (Libraries Unlimited, 1987) was published. This was followed by Romance Fiction: A Guide to the Literature (Libraries Unlimited, 1999), which was published as part of the Genreflecting series. This functioned as a guide to the romance fiction genre, including definitions, library information issues, and review materials to aid library selection and acquisition. A second edition was published in 2012. From the “professional tools” of the library information trade (Ross Reader 634) emerged Denice Adkins, Linda Esser, and Diane Velasquez’s scholarly research conducted into understanding public librarians’ perceptions of romance readers in Missouri (Perceptions). That study, and its subsequent publications, provide insights into the motivations of librarians for including romance fiction in library collections. They note that that despite their professional training in non-judgemental approaches to reading, librarians continue to regard romance fiction “as less worthy and low culture” (Adkins et al. Relations 61). Catherine Ross examines differing models of reading as they are understood by public librarians (Reader 635). She is critical of descriptions of the romance reader that depict her as a woman with little education and no prospects, calling it a “fiction” and one where “the romance reader is the Other” (Ross Reader 636). The potential conflict between the acknowledgement of romance fiction as being part of a library collection, but at the same time being disdained because of its readership, is the meeting point in this relationship.

The Barrier

There is sparse discussion on the placement of romance fiction in public libraries. Catherine Ross, using the language of a romantic liaison, says of romance fiction that public librarians use the practice of shelving genre books together as a method for actively courting the pleasure reader (Reader 634). Adkins, Esser, and Velasquez reiterate this sentiment saying that separate shelving for romance titles is a promotional strategy (Promotions 43) for librarians.

Shelving is used as a point of access into the collection. Author/title searches through a library catalogue are the most common way that readers access their selections, followed by browsing the shelves (Saarinen and Vakkari 738). The catalogue search requires, at the least, a basic record with author/title information for fiction to be findable, though this basic level of metadata provision is often not afforded to romance fiction, with incomplete catalogue records ranging from basic author-title entries to subpar metadata rendering each book unsearchable (Veros Matter). Catalogue records also contain corresponding shelf locations indicating the floor locations for collections. In selecting their fiction, romance readers search by author, blurbs, chapter samples, reviews, and a combination of factors so they can make their purchases (Australian Romance Readers Association 30). These strategies are similar to those used by readers of other fiction and align with “author’s name, text on the book’s back cover, and scanning the novel” that Saarinen and Vakkari (748) identify as the elements that are used for finding reading selections.

Browsing for items begins at the returned books shelf, new books shelf, and specific displays as well as alphabetical browsing. Libraries vary in their ordering systems for fiction, with some libraries separating their collections by genre and others maintaining a single alphabetised sequence ordered by author surnames. Catherine Ross says, “As an ordering principle, the alphabetic arrangement offers the serendipity of arbitrariness,” and with it comes the possibility of “all-inclusiveness” (Pleasures 1). This all-inclusiveness points to a situation whereby any fiction that is not included in the alphabetic arrangement can be considered as not fully part of the collection. This arbitrariness is further illustrated in Phyllis Rose’s The Shelf, where she decides to read every book on a specific fiction shelf (LEQ-LES) in the New York Society Library, allowing the library’s arbitrary, alphabetised ordering principle to dictate her choices. Forgoing the catalogue, she seeks out a single shelf. She writes that she read

Twenty-three books. Eleven authors. Short stories and novels. Realistic and mythic. Literary fiction and detective fiction. American and European. Old and contemporary. Highly wrought and flabby fiction. Inspired fiction and uninspired. My shelf covered a lot of ground. (235)

But what Rose doesn’t find is romance fiction.

In considering library shelf placement, it is important to take note of the medium of the shelf. Marshall McLuhan says that the “medium is the message” (19) and carries its own importance independently of its content. In the context of understanding shelving locations in public libraries, the shelves themselves are, in essence, “the medium”. As a medium, the shelves in a library are not neutral, but instead they impart cultural and societal cues about the items that they hold; the shelf conveys information through its patterns and placement, leading toward a perception upon the way that shelves reflect meaning in relation to the whole library space.

Lydia Pyne says that “bookshelves are dynamic, iterative objects that cue us to the social values we place on books and how we think books ought to be read” (1). Shelves communicate form and function and sturdiness in their ability to hold a book. Also, the shelf location of collections is in itself a system of applying cultural values to materials, often restricting and making collections inaccessible through the floor locations that they are given. McCabe and Kennedy identify “power spots” where books catch the eye, and transition zones, which are places of movement between sections of the library where library users pass through “and don’t look at products” (81).

Romance fiction is usually shelved on a paperback stand or in a separated shelving area. Wayne Wiegand noted that in 1998 a Chicago Tribune reporter wrote, “Librarians have historically been a tough sell for romances, often relegating the well-worn ‘silly’ paperbacks, uncatalogued, to a free-standing rack or donation shelf” (Wiegand 229).

Initial Attraction

Librarian Annie Spence in her book Dear Fahrenheit 451 writes love letters to books that are being considered for deselection at her library. This is the letter that she writes to Harlequin romances:

Dear Harlequin Romance Spinner Rack,

I never feel as susceptible to warts as I do when I’m weeding you guys. That’s not meant as an insult, but you do get around. I mean, you’re popular. (106)

This statement implicitly recognises the high circulation rates of romance fiction. Her letter, with its tongue-in-cheek tone, mentions “romantic possibilities”, “a full rack of full racks”, “an orgy of Rebel Ranchers, City Surgeons, Billionaire Daddys, and Gentle Tyrants”, “safe words”, “get your smut”, and “folks who can remember each of the eight hundred Harlequin titles they’ve read” (107). There is an underlying recognition that borrowers of romance novels read extensively and engage deeply with the fiction. However, in this Harlequin letter, she is not engaged with any of the narratives, instead keeping her distance, judging them by their aesthetics, their titles, and the rotating shelf that constrains them.

Spence’s letter can bring to mind the idea of a dalliance. The Oxford English Dictionary defines a dalliance as “Sport, play (with a companion or companions); esp. amorous toying or caressing, flirtation; often, in bad sense, wanton toying”, and the New Oxford American Dictionary defines dalliance as “a casual romantic or sexual relationship; brief or casual involvement with something”. The “dalliance” in the title of this paper serves as a metaphor and refers to the sense of librarians knowing that there is value in romance fiction, but only in a playful sense, one for leisure with a touch of wantonness and not as a committed part of library service delivery of literature worthy of critical analysis or as a literary experience (Frye Educated 265).

There is an inherent attraction between public libraries and romance fiction. For romance fiction, public libraries are a place to gain readers and cultural capital. The attraction for including romance fiction in a collection is that its readership is broad, allowing for libraries to engage with a wide cross-section of their communities along with reflecting everyday society’s reading practices and their popular culture engagements.

The Declaration of Intentions

The methodology involved visiting nineteen public libraries in New South Wales to examine the shelving practices for romance fiction in the broader context of their relationship to the rest of the fiction collections. Photographs were taken and field notes were made at the time of the visits. Semistructured interviews, following the same guiding questions, were conducted. Interviewees were identified by the library manager as having responsibility for collections and readers’ advisory services. As a result, eleven librarians were selected to participate in interviews, and they were drawn from seven of these public libraries. All of the interviewees were female librarians. The displays illustrated in this paper are representative of the practices across the libraries, taking into consideration the ease of capturing these photographically. The libraries represent the diversity of metropolitan, rural, coastal, and outback communities, covering a wide geographic area, and with a broad variety of socioeconomic indicators, including communities with significant Indigenous populations. All of the public libraries visited operate as local government council services. These libraries varied from single stand-alone buildings and libraries housed within community centres with mixed uses. The furthest libraries visited included a networked library system over eight hundred kilometres from Sydney and a stand-alone library over six hundred kilometres from Sydney.

Each library visited in this study had large romance fiction collections. Evidence of romance fiction in the library collections were a number of markers such as floor locations, subject headings as indicated in the library catalogue, a variety of stickers on books such as the heart symbol, the word “romance” and coded dots, such as those that Adkins, Esser, and Velasquez’s interviewees refer to as “the red dot district” (Relations 61), though one librarian interviewee pointed out that the service she worked in deliberately chose to code their romances with a blue sticker, as they didn’t want to play into the stereotype of red or pink stickers. Other sticker symbols include a high heel, and the heteronormative male-female couple holding hands. The heart sticker, of all the symbols, and alongside the word “romance”, is the most inclusive of all these markers. Other markers included collection signs over library shelves and at the end of their bays.

Point of Ritual Death

The observations in the libraries indicate that romance novels are placed at the margins of fiction collections. The shelf placement may reveal practices that do not treat romance fiction like most other fiction, but it is in the interviews that the idealized intent of librarian engagement with romance fiction becomes clear; rather than a committed interest in the genre as a literary experience, evidence of a passing dalliance emerges.

The Dalliance

Romance fiction on the shelves; they get around

Of the nineteen libraries that were visited, six were libraries that ordered their fiction by genre through separate shelving, often in paperback stands or spinners, or with stickers, with twelve ordering their fiction in an alphabetical sequence and one library having a combination of both alphabetized and genre-ordered fiction sections. None of the nineteen libraries had all their fiction interfiled, as they all treated their romance fiction differently to varying degrees. Of the nineteen libraries, seven libraries had a basic searchable author-title record accessible via the library catalogue; one library had part of its collection catalogued and some uncatalogued collections, which varied by individual branch; and of these seven libraries, only two added some of their romance holdings on the Australian national database TROVE. Ten libraries did not catalogue their romance collections beyond a generic “Romance Fiction” record, with hundreds of books given an accession/inventory number for the purposes of facilitating a loan, with four of those libraries omitting this basic record from being searchable on the library catalogue’s user interface. One library facilitated an honour-based book swap collection, exclusively romance fiction, that was not included in the catalogue.

Allocated space does not necessarily mean that an item is given equitable treatment in the library. This space allocation points towards a treatment that is different, not on par with the rest of fiction. Across the nineteen libraries, there were two different types of library shelves being used, with their placement of movement varying from high- to medium- to low-transition zones:

| High-Transition Zone | Medium- to Low-Transition Zone | |

| Shelves – spinners | 7 | 2 |

| Shelves – Fixed | 6 | 4 |

| *Other | 1 |

One library appears in both lists, as it had the romance collection stored in both fixed shelving and a movable shelf. Thirteen libraries housed their collections in high-transition zones of the library, with six housing their collections in difficult-to-access corners and nooks. Three of the libraries placed their romance fiction collection in “power” placements—that is, within twelve feet of the entrance and/or the information service desk. Librarian 3.3 says, “But we certainly don’t hide it away or anything. It has its very own stand, so it’s there.”

These “power” placements, however, could also constitute transition zones, as they are not destination shelves. Transition zones constitute spaces of movement, where users “don’t look at products” (McCabe and Kennedy 81). The items that are recommended for these zones are displays rather than whole collections.

The photos that follow show how romance fiction is place in library shelving. Figure 1 shows that placement may be in a high-profile location, at the entry of the library, but the romance fiction spinner sits alongside community information flyers and other ephemera, where it is in a different zone from the rest of the fiction. In this particular library, though the books were current and well ordered, there was no corresponding metadata visible on the catalogue’s user interface despite loans being facilitated through a barcode on each book.

Ten of the libraries only separated their category romance fiction collection—category romance novels such as those published by Mills & Boon. Of these libraries, five of them shelved this collection at the end of the fiction span, with Mills & Boon transcending the alphabet and being positioned as a twenty-seventh letter. Five of the six libraries shelving by genre separated the category romance fiction from the rest of the romance fiction collection, not alphabetically interfiling the thinner publication but instead placing the collection separately from the rest of both fiction and romance fiction. The sixth library using shelving by genre did not collect any category romance fiction.

Figure 2 shows how access to the category romance novels may be in a continuation of the fiction sequence on the same fixed shelving, but by being located on the bottom shelf, the collection is in an awkward and hard-to-access place. This library, too, did not provide any meaningful metadata for each novel, instead using a generic “Mills & Boon: [series name]” record and a corresponding floor location for romance paperbacks, which is visible on the catalogue’s user interface.

Eleven of the nineteen libraries had a physical separation of several paces to create a separate zone for their romance fiction collection. This had the effect of distancing the romance fiction not only from the fixed shelves of the library but also from the surety of the fixed medium, onto shelves that are movable, spinnable, and less searchable.

Librarian 1.1: “Well, that’s where, those that are shelved separately, they are just romance. They are your light romance novels. So, we are figuring that people aren’t, or people will know to go there because that is what they read, or they don’t want that style, but they might go with the one that is a longer story with a romance thrown in.”

Librarian 1.2: “Well, some romance fiction is interfiled and has a heart on it. The special sticker. And the Mills & Boon–type smaller publications—they are shelved separately. Maybe because they are… Some people who borrow a basket full of them and just pick a foot of romance off the shelf and just take them home…”

Librarian 3.2: “Yep. Only the Mills & Boons are shelved in the revolving stand.”

In Figure 3, the fixed shelves are separated from the romance shelves with a wide corridor. In this particular library, each book has its own unique catalogue record, which is searchable by the author/title. However, there is no corresponding linked record held on the national database.

These romance fiction collections are highly read, with one interviewee stating that at the time of the interview, 21 percent of the fiction collection was out on loan (a seasonal low), however, 30 percent of the romance fiction was out on loan—a higher figure than any of the other fiction genres. She says:

Librarian 2: [on whether romance fiction is in high-rotation collections] “Never touch. Never touch [gesticulations showed that she meant they never touched the shelves]. And in fact, we have a branch where they are commonly stolen.”

Objectifying the form:

The materiality of the book is an important consideration. There is a focus placed on the format, the size, and the weight of romance fiction.

Librarian 6: “…like Barbara Cartland, or bush romance, or supernatural romance. An actual book—like that [motions], you know, it has a bit more weight to it. It will sit on the shelf, and you can actually see what it is called without too much difficulty. They get put in the general collection, the normal adult fiction collection. They don’t get a heart sticker.”

The term “normal” positions other romance novels outside of the fiction collection.

Librarian 5: “I suppose that type of format doesn’t last well on the shelves, so there is quite a high turnover.”

Librarian 1.1: “In amongst that, we do have the thicker ones. They are still the small ones, thicker ones, which are still primarily romance-based, so we have got a lot of those in there as well. But then you have got the ones that are a story that happen to have a romance bend to it, but it is not really the primary focus of the book—they will be filed in the general fiction section, but they will have a romance sticker on them. So, we will have a little heart sticker on the romance…”

Where the materiality of the book is considered important, the content is often not considered as an important factor. The library in which this interview took place had titles from Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton series in two different floor locations/shelf placements. The Trade Paperback B–sized Bridgertons were shelved in General Fiction, and the mass-market-sized Bridgertons were shelved in the Romance Fiction section of the library.

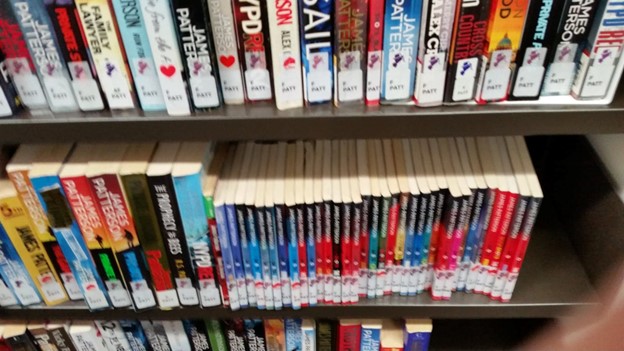

In another library that was visited, the Crime Fiction titles of James Patterson were all interfiled together regardless of their size, i.e., trade paperback B and slimmer mass market size (Fig. 4). However, even though The Bachelorette–branded editions of category romance titles (printed in trade paperback B size) by Michelle Douglas, Marion Lennox, Emma Darcy, and Barbara Hannay were interfiled in the alphabetised general fiction collections, the same titles and/or authors’ works in mass-market size were shelved separately from the rest of their own works and the general fiction collection.

Librarian 5: “They are quite little books, both in the width and the size, and if they were integrated into the normal collection, they would probably get pushed further to the back of the collection, so that’s probably a reason as well.”

Book browsing is a casual relationship

Browsing bookshelves is a known search strategy for library users. Making sense of how librarians consider this practice and the way they consider browsing collections emerged through each of the interviews that were conducted. Some browsing collections are also catalogued.

Librarian 5 indicated that the picture books, CDs, and DVDs were all browsing collections, along with the romance fiction collection, but that only the romance fiction browsing collection was not catalogued—in a sense, being ghosted. Librarians justified the emphasis on making romance fiction collections browsing collections:

Librarian 1.1: “I guess it allows for more serendipitous browsing. You are not locking people into, you know, ‘If you are a mystery [reader] you must go to the mystery section’, or you might go, ‘well, I’m not going to go to the romance section because I don’t read romance’, but if they were searching along, they might actually see and think, ‘well, actually, that doesn’t look too bad’, you know.”

Librarian 1.2: “We like to cater for the browser as much as the person who is going to look things up on the catalogue.”

Librarian 4: “I think partially…the people who access Mills & Boon just shelf browse.”

But the uncatalogued browsing collection practice caters to only the physical browser. It does not offer access to the library user who searches catalogues across digital book discovery tools to locate their fiction before considering travelling to their library. Romance readers use the same search strategies as other fiction readers (Australian Romance Readers Association 30; Saarinen and Vakkari 748). The responses that librarians gave seemed to suggest that romance readers are undiscerning in their selections, thus the librarians’ attention to the collection may be guided by their misperception of reader behaviours.

Physical appearance is important in a dalliance, and in the library setting, it is clear that size and appearance do matter to the librarian,

Librarian 1.3: “I think things were easily identifiable, like those pink Mills & Boon, you think that is the sort of fiction that you like, people would just walk along and pluck them off the shelves.”

Continuing with the metaphor of dalliance, the reader “plucking” books off the shelf without checking the blurb is considered as undiscerning.

Librarian 5: “…So those ones aren’t actually catalogued, so all we do is stamp them with an ownership stamp and do the sticker and they’re just from people’s donations and they just go on that shelf and it’s on that carousel. It’s just a browsing collection. So…”

Dallying with a collection indicates a lack of care, and a lack of attention, especially when there is force, a “whack”, applied to the novels:

Librarian 6: “If you are talking about Mills & Boon–style paperbacks—no. We get given those by the boxload. And we have a section where we put them. They are not catalogued as separate entities. There is just a generic ‘romance paperback’ [catalogue record] and we just whack them on.”

You don’t h/look up romance novels

In the dalliance, though the hook-up is inevitable, there is no deliberate searching or seeking out. Librarian 1.2 suggests that the borrower doesn’t “actually want to go through that selection process”, implying an indiscriminate approach to reading choices, as do other librarians:

Librarian 1.3: “I don’t think that when people come in to borrow those books, they take it off the shelf, read the back cover or whatever to see what it’s about. I think they just take them.”

Librarian 2: “See…I guess the borrower [is not] borrowing for the author and title—they’re borrowing more for that format. The format of the book. They know that that is what they will find in that book.”

There are instances in the interviews that the relationship between the catalogue record and the shelf placement is disregarded, as the reader themselves is not viewed as someone who would consider searching for romance novels by their titles or by the author, despite these being stated elements that the reader uses in their decision-making (Australian Romance Readers Association).

The ability to search the library catalogue is intrinsic in service delivery for public libraries. However, it is not a practice that is consistently adhered to when considering romance fiction collections:

Librarian 5: “In the years I have worked in a public library, I haven’t had someone come up and say, ‘Can you look up this author, and you know she’s a Mills & Boon author’. I’ve never had that one. So I suppose if we are getting asked that question, it would make us re-evaluate that sort [creating searchable catalogue records] of decision.”

Here, the readers’ lack of requests for specific authors from the romance collection is given as the reason that the catalogue record is not added. One librarian noted that lack of catalogue records impacted their own ability to conduct professional searches:

Librarian 3.1: “You know, if they would say, ‘I want to read romance fiction’, one of my tactics was—‘OK, follow me to the fiction section, and see that love heart on those books’…[laughs]…”

Assumptions are made as to how people select their romance novels, however, these assumptions necessitate expert and skilful library professionals to use lesser approaches to meet the needs of library users requesting romance fiction.

The Scarlet Sticker 💗

In the dalliance, there is a wink to the relationship, a way of publicly stating that dating is fine, however, it is also a public marking of a relationship that is not worth moving forward and for others to take note.

Librarian 7.1: “I think [putting a sticker on the book] was just to assist people to know whether a blue dot was suspense and a pink dot was romance and just really to help the borrowers to select, especially when there was very limited catalogue records.”

The suggestion is that the stickers are a legacy practice coming from a time that fiction catalogue records did not contain enriched metadata. The sticker system assisted library staff in finding fiction, as well being a system that guided the library users. The implication in the interviews was that people were wanting to have coded systems on the actual books so that they could find materials in a way that made sense to them. This notion of the legacy practices is confirmed by Librarian 7.1, who continues, “And now, because we primarily buy our records in through Libraries Australia, the records are much superior to anything we might have had twenty years ago”.

Librarian 6, who had noted that romance fiction in the normal adult fiction collection is not marked by a heart sticker, also noted that she did not know why that was the case. This action of marking or not marking a book is a system of applying cultural capital to fiction. And here, the mark of the heart could be considered a scarlet marking, one where the indication may bring down the cultural value of the book.

Librarian 2: “Well, some romance fiction is interfiled and has a heart on it. The special sticker.”

The “special” sticker is a way of marking the interfiled book for the romance reader, but it also is a way of signalling to those, who in the words of Eric Selinger (308) have a “disdain for popular romance fiction”, that this book may not be for them.

Librarian 3.2: “So [redacted staff name] doesn’t like that heart [sticker] for romance, because it could be a sophisticated romance story, like with family, tension or something.”

Here, the marking of a novel with a heart sticker is considered a negative—one that detracts from a story that is considered sophisticated, thus, anything that has a sticker applied to it could be considered not sophisticated. Librarian 6 reaffirms this with her statement that “an actual book” is placed in the “normal” or “general” collection, as though a book not in the “general collection” is somehow not “normal”.

Floor placement and genre identification marks can create quandaries. Heart stickers on books that are already shelved under a “Romance” banner are reductive, however, the librarian here is clear that romance fiction, shelved in the romance collection and written by Australian authors, would not merit an Australian sticker, or even an Indigenous author sticker, but would continue to have a heart sticker.

Librarian 1.3: “We have a genre for Australian titles, but I think romance overrides the Australian … [and] I don’t think we have an Indigenous sticker on all the Anita Heiss books”.

Wanton toying

Even with librarians who described romance fiction in a positive tone, there is an underlying sense that the fiction is only for play or toying and that this arises from a position where there is a hierarchy of fiction:

Librarian 4: “I think for a while romance was kind of a… Librarians can be total snobs, and you will find as an industry, we can be very sort of highbrow about what we consider literature and stuff like that, and I think we tend to forget that reading is meant to be entertainment. You know, and people should read widely and should read whatever they like.”

This toying, however, can often cease being playful and becomes a tone of “derision” (Perceptions):

Librarian 6: “I think I get a bit elitist when it comes to books, and, you know, those ones…when I look at them, I go “ughh” [a dismissive “ugh”]. They are just romance. They are not worth my time or my b[udget]…”

When you give it away free

This question of financial resources seems to be the go-to answer for all the respondents in explaining their acquisition and treatment of romance fiction. The budget line is restricted, so the easiest item not to give value to is the collection that has been built through community contributions.

Librarian 7.1 explains that romance fiction is not put on the display shelves “because we are showcasing the other materials. Stuff we have paid for”.

Librarian 4: “[The librarians in charge of selection] actively will not buy romances, and what they will do with the Mills & Boons is they will put them away as ‘Take one. Just take it.’ And they will restock their shelves with [romance fiction] donations to be taken. And they don’t encourage readers to borrow them or for it to be an active part of the collection.”

Librarian 5 uses the term “disposable” to refer to romance fiction. She “would recommend it to people who wanted something like that, but I know some people think that it is probably not proper reading…and that it is not seen as, you know, proper literature or to have literary merit…”

Caressing flirtation

Understanding the appeal factors of fiction is a standard practice in librarians’ professional work. Here the librarians express the reasons that a reader may have for reading romance fiction.

Librarian 7.1: “Primarily women, just about all of the borrowers of that collection are women, who just want something light to read to fit in with whatever else they do.”

Librarian 1.3: “Because they are quick to read. I think. I think they enjoy a nice, nonthreatening story with a happy ending.”

Librarian 1.3: “I think just as …a feel-good story. Yeah. And perhaps they [the reader] don’t want to be challenged. I suppose that is what I mean.”

Librarian 6: “Oh, pure entertainment! Pure relaxation.”

These are positive and supportive statements on reading practices, however, once they are interrogated through the use of the concept of “dalliance”, they reveal that romance fiction is not considered to be meaningful. These findings show how the perceived unsuitability of romance fiction leads to its shelving placement in transition zones, tight corners, beyond the alphabet and on unstable, spinning paperback carousels rather than on shelves of substance. Their haphazard shelving intersects with their inconsistent catalogue metadata. From this evidence, the dalliance is clear and the fractures in the relationship between public librarians and romance fiction become apparent.

Recognition

The recognition is the point at which a discussion needs to take place as to why the relationship between romance fiction and librarians is still developing, to come to an understanding of past problematic practices and that reparations still need to be made so as to move forward for a better future with each other. Phyllis Rose says, “Fluffy entertainments morph into weighty artifacts. If we’ve learned one thing, it’s that cultural objects are malleable and change in time” (20). Perceptions of romance fiction have shifted over time, and romance fiction’s cultural importance is being understood beyond its historically negative aesthetic. The interviews with the librarians reflect an acceptance of romance fiction as being escapist, ephemeral, light, for women, as nonthreatening, positioned as encouraging literacy, but it is not considered to be literary or meaningful.

Romance fiction stories, with their optimistic endings, are an idealized world, as is the public library, where the illusion of meeting the reading needs of a broad community is a strong part of the professional field’s rhetoric.

The data collected in this study do reflect that librarians, in their consideration of the role of the literature that is available in their library, allude that the reading of romance fiction continues to be of a lesser value than the reading of “normal” fiction, even if it is by a small degree. This valuing can be seen through the application of the metaphor of dalliance and the examination of the shelving medium that contains the fiction, with the message that is conveyed through the varied treatments of the fiction on these shelves.

The interviews show that librarians may support collecting and making available romance fiction in the abstract, but practices are driven by legacy decisions, a negative perception of the novels’ content and substance, or of their monetary value as well as their propensity to be donated (Veros, Selective). Books bought using the library budget seem to be valued more highly than the library communities’ contribution of donated materials that have been accepted into the public collection.

Serendipitous browsing is often presented as a way to give readers broad options. However, this study has shown that the practices of librarians can lead to two types of “locking outs”. The reader of romance fiction can be locked out from other options, because their own reading is not considered to be part of the alphabet, constraining them to the spinning shelves, the corner shelves, the transition zones, and inaccessible shelves. The second “locking out” occurs because the reader of general fiction is also not given the opportunity to discover and engage in a fiction that is recognised as being emotionally charged, that is nuanced literature focusing on intimacy, that follows the minutiae of main characters seeking romance to free them from their encumbered lives (Regis 30), leaving these readers confirmed in their belief that romance fiction is a lesser fiction.

An optimistic ending

“A romance novel is a work of prose fiction that tells the story of the courtship and betrothal of one or more heroines. This definition focuses on the narrative essentials of the romance novel— those events, including the happy ending, without which there is an incomplete rendering of the genre.” Regis (22)

Exploring the metaphor of “dalliance” through the use of Pamela Regis’s eight essential elements of romance fiction as a “thinking tool” from the field provides a framework for understanding the level of commitment made to specific collections within a library, the assumptions that are being made about the literature by librarians, and the value that is applied to the collection. Dalliance becomes the measure of the degree of engagement with the romance fiction—whether it is a fun fling, a pleasurable one-night read, or a meaningful literary commitment.

Northrup Frye writes that “the conventions of literature contain the experience; their formal laws hold everywhere; and from this point of view there is no difference between the scholarly and the popular in the world of words” (Educated 266). Through a dallianced examination of the shelf placement of romance fiction, the interaction between physical spaces and the catalogue records, and interviews with librarians, the evidence shows that romance fiction is treated differently from the other fiction collections in the library “world of words”. This treatment can be seen through data incompleteness, placement away from other fiction, and personal feelings overriding professional practice, showing that romance fiction continues to be considered a lesser fiction, one that is not valued to the same degree as other fictions.

For now, there is no betrothal scene between romance fiction and public libraries—the relationship remains a dalliance. Instead, there is a continued discussion of how libraries could move towards a more committed relationship. Until then, libraries cannot be the idealized society they present, as they are an incomplete rendering of the communities they are trying to reflect. This new understanding could be seen as a Happy for Now, keeping within its sights a Betrothal. A final conclusion with the library moving forward.

Acknowledgments

An “Under Review” copy of this paper appears in Veros, Vassiliki Helen. What the Librarians Did: The marginalisation of romance fiction through the practices of public librarianship. 2020. University of Technology Sydney, Doctoral Dissertation.

[i] UTS HREC Approval number: 2014000622 for the project title: The marginalisation of romance fiction through the practices and policies of libraries and cultural institutions.

Works Cited

Adkins, Denice, Linda Esser, and Diane L. Velasquez. “Perceptions of Romance Readers: An Analysis of Missouri Librarians.” Paper presentation at the Library Research Seminar III, Kansas City, Mo. (October2004).

Adkins, Denice, Linda Esser, and Diane L. Velasquez. “Promoting Romance Novels in American public libraries.” Public Libraries, vol. 49, no. 4, July 2010, pp. 41–48.

Adkins, Denice, Linda Esser, and Diane L. Velasquez. “Relations between librarians and romance readers: a Missouri survey.” Public Libraries, vol. 45, no. 4, July 2006, pp. 54–64.

Australian Romance Readers Association. 2018 Australian Romance Readers Survey. 2018, http://australianromancereaders.com.au/about/. Accessed 1 Mar 2019.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Routledge, 2013.

Chelton, Mary K. “Unrestricted body parts and predictable bliss: The Audience Appeal of Formula Romances.” Library Journal vol. 116, no. 12, 1991, pp. 44-49.

Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism. 1957. New York: Atheneum, 1969.

Frye, Northrop. The Educated imagination and other writings on critical theory, 1933–1962. Vol. 21. University of Toronto Press, 2006.

Goulding, Anne. “Libraries and social capital.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, vol. 36, no. 1, 2004, pp. 3-6.

Linz, Cathie. “Exploring the World of Romance Novels.” Public Libraries vol. 4, no. 3, 1995, pp. 144-151.

McCabe, Gerard B., and James Robert Kennedy. Planning the modern public library building. Libraries Unlimited, 2003.

McLuhan, Marshall, and W. Terrence Gordon. Understanding media: The extensions of man. Corte Madera, Ginko Press, 2003.

“Dalliance.” New Oxford American Dictionary. Eds. Stevenson, Angus, and Christine A. Lindberg: Oxford University Press, January 01, 2011. Oxford Reference. Date Accessed 1 May. 2019

“Dalliance, n.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2019, www.oed.com/view/Entry/46978. Accessed 1 May 2019.

Pyne, Lydia. Bookshelf. Bloomsbury, 2016.

Ramsdell, Kristin. Romance Fiction: A Guide to the Genre, Libraries Unlimited, Englewood, 1999.

Regis, Pamela. A natural history of the romance novel. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

Rose, Phyllis. The Shelf. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2015.

Ross, Catherine Sheldrick. The Pleasures of Reading: A Booklover’s Alphabet. ABC-CLIO, 2014.

Ross, Catherine Sheldrick. “Reader on Top: Public Libraries, Pleasure Reading, and Models of Reading.” Library Trends, vol. 57, no. 4, 2009, pp. 632–656.

Saarinen, Katariina, and Pertti Vakkari. “A Sign of a Good Book: Readers’ Methods of Accessing Fiction in the Public Library.” Journal of Documentation, vol. 69, no. 5, 2013, pp. 736–754.

Selinger, Eric Murphy. “Rereading the romance.” Contemporary Literature, vol. 48, no. 2, 2007, pp. 307-324.

Spence, Annie. Dear Fahrenheit 451: A Librarian’s Love Letters and Breakup Notes to the Books in her Life. 1st ed., Flatiron Books, 2017.

“Trove”. Trove, 2019, https://trove.nla.gov.au.

Veros, Vassiliki. “A matter of meta: Category romance fiction and the interplay of paratext and library metadata.” Journal of Popular Romance Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2005. https://www.jprstudies.org/2015/08/a-matter-of-meta-category-romance-fiction-and-the-interplay-of-paratext-and-library-metadataby-vassiliki-veros/.

Veros, Vassiliki. “The selective tradition, the role of romance fiction donations, and public library practices in New South Wales, Australia.” Information Research: An international electronic journal, vol. 25, no. 2, 2020, paper 860. https://informationr.net/ir/25-2/paper860.html.

Wacquant, Loic JD. “Towards a reflexive sociology: A workshop with Pierre Bourdieu.” Sociological Theory, vol. 7, no. 1, 1989, pp. 26-63.

Wiegand, Wayne A. Part of Our Lives: A people’s history of the American public library. Oxford University Press, 2015.