Compared to the better-known genre of “boys’ love” manga, the Japanese tradition of yuri romance manga has received limited scholarly attention in the West. Also known as “girls’ love” manga, yuri deals with romantic relationships between girls or women, most often teenagers or young adults. Although the genre’s roots go back to the early twentieth century, it is only since the 2010s that yuri manga has started to be regularly translated and published in English, giving rise for the first time to a substantial Anglophone audience who identify themselves as fans of yuri media. Organised around online spaces such as The Holy Mother of Yuri, Okazu, Dynasty Reader, and the r/yuri_manga and r/yurimemes subreddits, these communities devote themselves primarily to the distribution, discussion, and evaluation of Japanese yuri manga and anime, although in recent years their members have also started to take an interest in lesbian comics and webtoons from Thailand, China, and South Korea.

While these communities are defined by their shared love of yuri media, their discussions are marked by recurrent notes of discontent. Their most active users celebrate the genre’s depictions of love between women, but they also frequently express frustration with what they see as its failings or limitations: its focus on high school settings, its refusal to clearly distinguish between platonic homosocial friendship and romantic homosexual love, and its lack of engagement with the politics of queer identity. In particular, users often complain about so-called “yuri bait”: yuri stories that they interpret as lesbian romance narratives but that culminate in affirmations of friendship between women rather than explicit confessions of romantic or sexual love (DotBig2348). Such stories often draw upon older models of “passionate friendship” between women, and the discontent of their Anglophone readers reflects the gap between these modes of female homosociality and the romance cultures that have replaced them.

This article investigates the Anglophone reception history of yuri manga by surveying those yuri works that have been translated into English and the ways in which their online fan communities have responded to them. My analysis of the genre is based on a corpus of 220 volumes of Japanese yuri manga translated and published in English between 2007 and 2024; all quotations are drawn from these translated editions, as they represent the form in which Anglophone audiences are most likely to encounter them. As their responses suggest, Anglophone fans generally understand yuri as a form of LGBT+ media and evaluate it using the same criteria they apply to Western lesbian fiction. As I shall discuss, however, the terms yuri and ‘lesbian romance’ are not interchangeable. Much of the frustration expressed in Anglophone yuri fandom spaces results from tensions between Western and Japanese media traditions depicting same-sex intimacy between women, making the genre a valuable case study in the cross-cultural reception of queer romance media.

Assimilationists and Transculturalists: Anglophone Scholarship on Yuri Media

The extant scholarship in English on yuri media is limited. James Welker, who has written extensively on Japanese lesbian culture and history, briefly discusses yuri in a 2008 essay in AsiaPacifiQUEER:Rethinking Genders and Identities. Crucially, he notes that “yuri was not synonymous with rezubian[1] [lesbian]” and that Japanese women who sought out yuri relationships were looking for love with other women, but not necessary for sex (Welker, “LiLies” 53–4). The practises of the early Anglophone yuri fandom are described by Yaritza Hernandez in her 2009 essay “The Impact of Globalization on Yuri and Fan Activism,” and the origins of the genre, along with its distinctive approaches to gender and sexuality, have since been mapped out in Nagaike Kazumi’s article “The Sexual and Textual Politics of Japanese Lesbian Comics” (2010), Deborah Shamoon’s Passionate Friendship: The Aesthetics of Girl’s Culture in Japan (2012), and Verena Maser’s PhD thesis, “Beautiful and Innocent: Female Same-Sex Intimacy in the Japanese Yuri Genre” (2013). All of these, however, were written at a time when yuri media was still largely unknown outside Japan. They predate the English releases of pivotal yuri manga titles such as Milk Morinaga’s Girl Friends (2006–2010, translations 2012–2013) and Saburouta’s Citrus (2012–2018, translations 2014–2019), which proved foundational for the development of Anglophone yuri fandom. Thus, Andrea Wood’s article “Making the Invisible Visible: Lesbian Romance Comics for Women” (2015) does not mention yuri, even though the Western comics she discusses clearly owe it a considerable stylistic debt. The lesbian love scene that Wood singles out for praise in the American comic Clockwork Angels, for example, would be entirely ordinary in a work of Japanese yuri manga (Wood 308).

More recently, Hannah Dahlberg-Dodd’s “Script Variation as Audience Design” (2020) has explored the ways in which Japanese yuri magazines rhetorically frame their assumed audiences, but her article deals specifically with their domestic reception: to Western audiences encountering yuri in English translation, the Japanese script variations described by Dahlberg-Dodd are effectively invisible. Marta Fanasca’s “Tales of Lilies and Girls’ Love: The Depiction of Female/Female Relationships in Yuri Manga” (2020) has discussed some modern yuri titles but does not touch on their reception history. Finally, Maser’s and Fanasca’s 2020 articles discuss the translation of yuri manga in Germany and Italy, respectively. Their focus, however, is primarily on the difficulties that the genre poses for its German and Italian publishers rather than for its readers.

Of the critics who have written on the Anglophone reception of yuri, the most directly relevant to this article is Dale Altmann’s 2021 MA thesis “Cross-Cultural Reception in the Western Yuri Fandom.” Altmann argues that there are two main paradigms through which Western audiences approach yuri: an “assimilationist” approach, in which yuri is assessed (and usually found wanting) by the standards of Anglophone LGBT+ fiction, and a “transcultural” approach that seeks to understand yuri in terms of what Altmann calls “the specific cultural background of the genre” (6, 15). Many of the debates within Western yuri fandom thus hinge on the question of whether yuri should be understood on its own terms or evaluated by the same standards as Western media. Altmann examines these debates in relation to the Western fandom for yuri “visual novel” video games, and in this article, I extend this analysis to the reception of yuri romance manga.

Much critical writing on yuri can be understood as either “transcultural” or “assimilationist” in tendency. Rika Takashima’s article “Japan: Fertile Ground for the Cultivation of Yuri” (2014) describes yuri as an inherently Japanese form, tied to the specific contexts of Japanese cultural history: Takashima writes that “Americans are able to accept yuri because they see it as a product of Japanese culture, but yuri works created outside Japan would not receive the same reception.” Similarly, Ka Yi Yeung’s 2017 master’s thesis “Alternative Sexualities/Intimacies? Yuri Fans Community in the Chinese Context” examines the way that Chinese yuri fans value the genre precisely because its distinctive model of same-sex intimacy provides an alternative to both the heteronormative structures of Chinese society and to the norms of the Chinese lesbian subculture. Meanwhile, the works of Katherine Hanson, Ana Valens, Natalie Fugate, and Erica Friedman all approach yuri from an “assimilationist” standpoint, evaluating the genre in terms of its success or failure to represent what they understand to be authentic “lesbian identity.” As I shall discuss, the same divisions are visible in Western yuri fandom, in which many of these authors are themselves active participants.

In this article, I draw upon these works to briefly sketch out the tropes and conventions of the yuri genre and to highlight some key differences between Japanese yuri media and Anglophone lesbian fiction. I then discuss the ways in which these differences give rise to a mismatch between the genre norms of yuri and the expectations of many Anglophone readers. Finally, I discuss these debates in relation to a specific work of yuri manga: A Tropical Fish Yearns for Snow (2017–2021) by Hagino Makoto.

Lily Love: Defining Yuri

In Japanese, the word yuri means “lily.” The term Yurizoku (‘lily tribe’) as a euphemism for lesbians dates back to the 1970s, but the symbolism that it draws upon is substantially older (Friedman, By Your Side 18; McLelland 147). It derives from the Meiji (1868–1912) and Taishō (1912–1926) eras, during which elite Japanese families began sending their daughters to Western-style single-sex boarding schools; many of these were Christian foundations dedicated to the Virgin Mary that incorporated her flower, the lily, into their iconography (Shamoon 31–32). As Shamoon and Jennifer Robertson note, Japan had no previous tradition of schooling for girls, and the emergence of this new female life-stage between childhood and marriage—the shōjo—was regarded as deeply troubling and potentially socially disruptive (Shamoon 2; Robertson 63–65).

Cloistered in all-female environments behind lily-engraved gates, Meiji- and Taishō-era schoolgirls became famous for the intensity of their “passionate friendships,” characterised by feelings of akogare—a word translated by Hanson as “adoration” and by Friedman as “admiration tinged with desire” (Shamoon 37; Hanson; Friedman, By Your Side 57). In prewar Japan, these friendships achieved semi-institutional form as so-called ‘Class S’ relationships. The archetypal ‘S relationship’ was between an older schoolgirl (sempai) and a younger schoolgirl (kouhai) and acted as a kind of practise marriage in which the sempai was expected to court her kouhai and win her affections, often with the aid of love letters or flowers. The sempai would then act as the kouhai’s mentor, instructing her in the proper performance of elite shōjo femininity (Shamoon 33–38; Robertson 68–69; Akaeda 186–201; Pflugfelder 147). In keeping with prevailing gender stereotypes, such ‘S’ relationships were idealised as supposedly “pure” and spiritual bonds, in sharp distinction to the intense physicality that was thought to characterise male homosexuality (Akaeda 189; Robertson 68–69; Pflugfelder 148). They were, however, expected to end after graduation and marriage.

Crucially, in prewar Japan, love relationships between girls were often seen as normative rather than aberrant (Pflugfelder 142, 147). Akaeda Kanako cites one school president as estimating that seventy to eighty percent of schoolgirls engaged in such relationships, and Japanese girls’ magazines of the period were so deluged with letters about Class S relationships that they had to beg their readers to stop sending them in (Akaeda 195, 198–9). As Akaeda and Shamoon note, in Meiji-era Japan marriage among elite families was traditionally arranged and dynastic, and Western ideals of romantic love (ren’ai) as a free choice between individuals were still a recent and contentious cultural import. Girls frequently found such ideals easier to realise in their relationships with each other than within the more strictly hierarchical context of their arranged marriages with men—and the symbol of such love was, of course, yuri, the lily (Akaeda 189, 196; Shamoon 31–32). Such relationships thus came to be viewed not as a deviation from ordinary close friendship between adolescent girls, but as the normal form that such friendships might be expected to take (Akaeda 195–96).

The American occupation of Japan brought in coed high schools, with the result that traditional shōjo culture withered after the war, and the Class S system declined with it (Shamoon 2–3, 83; Maser, “Beautiful” 46; Pflugfelder 174–75). However, its ideals cast a long shadow, and exerted a strong influence over yuri manga as the genre coalesced in the 1990s. Some influential yuri franchises, such as Maria Watches Over Us (1998–2012) and Strawberry Panic! (2003–2007), were set in fictional Catholic girls’ schools in which versions of the Class S system were imagined as having survived into the modern era. When a character in the yuri series Whispered Words (2007–2012) is revealed to be a yuri author, his study is shown to be packed with prewar girls’ magazines, with the implication that he draws inspiration for his yuri stories from the Class S material they contain (Ikeda, vol. 1).

The modern yuri manga genre is unusual in not being confined to a single demographic. Most Japanese manga magazines are classified as shōjo (aimed at girls), shōnen (aimed at boys), josei (aimed at women), or seinen (aimed at men); yuri stories can and do appear in all four, and since 2003 a growing number of yuri works have also been published in dedicated yuri magazines such as Yuri Shimai, Yuri Hime, and Pure Yuri Anthology Hirai, which are marketed to both male and female readers (Bauman). Editorial control over manga magazines is tight, and the material they publish is strictly constrained by what their editors believe their audiences want to read. Some yuri stories published in seinen magazines are pornographic in character, but many are not, and it is common for seinen magazines to publish yuri series with a strong focus on romantic yearning and little or no sexual content: both Girl Friends and Whispered Words first appeared in seinen magazines. While the genre has diversified in recent years, both seinen yuri and the works published in yuri magazines still often retain the traditional Class S focus on emotionally intense relationships between adolescent girls, unfolding within single-sex environments in which same-sex love is presented as normative and the boundary between passionate friendship and romantic love is extremely ambiguous (Dahlberg-Dodd 358; Maser, “Beautiful” 23–5, 115).

Writing in 2006, yuri mangaka Shinonome Mizuo connected her depiction of such relationships to her own school experiences:

I actually remembered back to my own time at school while working on this. There was a girl in the same grade as me who was smart, friendly, cheerful and on the track team. I was infatuated with her. I think that because womanhood itself is delicate, and changes so much with things like marriage and giving birth, love between two women might be seen as ephemeral, shining, and gentle. (Shinonome, author’s note)

Within this paradigm, yuri is specifically linked to the “ephemeral” context of adolescence and shōjo identity, before “womanhood” is forever altered by the experiences of “marriage and giving birth”—hence the genre’s heavy focus on high school settings. As Maser notes, yuri has traditionally been “a genre about girls living in a beautiful, dream-like world with a hint of sadness as the protagonists’ youth draws to a close” (“Beautiful” 23).

Consequently, as a succession of writers have noted, ‘Class S’ and yuri cannot be understood to simply mean “lesbian” (Shamoon 35; Welker, “LiLies” 53; Maser, “Beautiful” 2, 115; Nagaike; Fanasca, “Tales” 57; Yeung 7). Indeed, the extent to which Western terms such as gay and lesbian are applicable to Japanese cultural constructions of same-sex love has been a topic of considerable debate among scholars and activists (Welker, Transfiguring 80, 93). Japanese culture has historically maintained a sharp divide between private sexual preference and public role, and a preference for same-sex partners has consequently not been viewed as constituting an “identity” in the modern Western sense, though the question of whether this constitutes a state of toleration or of oppression is extremely contentious (Nakamura 269; McLelland 174–80; Khor passim). In Japanese rezubian is an English loanword, as is identity (aidentiti): Welker notes that “a significant amount of written Japanese lesbian discourse has been translated from or is based on seminal lesbian works in English and other languages” and that when self-identified Japanese lesbians place themselves within a larger lesbian history, it is largely a Western history stretching back towards Sappho and Ancient Greece (Welker, ‘Telling’ 370; see also ‘Toward’; Transfiguring 68-72, 122-5). Yuri, by contrast, draws upon culturally specific models of female homosociality that can include same-sex sexual desire but are not defined by its presence. As Welker observes, even though the word resubian was already in use in prewar Japan, it was seldom applied to S relationships, which were seen as quite distinct from Western-style resubian ravu (‘lesbian love’) (Welker, Transfiguring, 67–70). As a result, and to the frustration of some Western readers, much yuri media is genuinely uninterested in whether its heroines are lovers or just good friends.

Maser notes in her discussion of yuri translation that “the omnipresent Japanese term suki—which can mean to love, like, or care for—can pose a challenge” (“Translated” 161). When one girl tells another she likes (suki) her, this can be understood as anything from an affirmation of friendship to a declaration of romantic love—an ambiguity that older yuri manga, in particular, often makes little attempt to clarify (Maser, “Beautiful” 25; Yeung 3). In Maria Watches Over Us, for example, every story revolves around relationships between girls, most of which take place within the context of Class S style relationships at a fictional Catholic girls’ school: its heroines hold hands, go on dates, and sometimes kiss, but the story never clarifies explicitly which, if any of them, think of themselves as ‘lesbian couples’ or are involved in sexual relationships. Similarly, Voiceful (2006) culminates in a characteristically ambiguous confession of affection:

“Hina . . . do you . . . like me?”

“Yeah. I like you a lot, Kanae.”

On that day . . . we became a lot closer than we ever had. (Nawoko, ellipses in original)

This could be interpreted as a mutual confession of attraction marking the beginning of a lesbian relationship (with “we became a lot closer” as a euphemism for sex), but it can also be read as a simple affirmation of friendship. Crucially, the underlying emotional logic of the story—in which Kanae helps Hina with her grief over the death of her beloved sister at the hands of her abusive father—fits equally well with either reading. Within the generic conventions of yuri, the fact that Hina and Kanae love one another is more important than the specific form through which that love is expressed.

As Takashima notes, this ambiguity was regarded by its original target audience as a positive trait: “Within the sphere of yuri, fans have a propensity for reading between the lines, picking up on subtle cues, and using their own imaginations to weave rich tapestries of meaning from small threads” (Takashima). Indeed, yuri sometimes functions less as a sexual orientation than as a methodology for interpreting the world, one that is attuned to the potentially romantic dimensions of any and all relationships between women—a perspective both illustrated and satirised by the yuri-loving protagonists of works such as Morishima’s story “Incomplete Fujoshi” (2009), Kinosaki’s “Yurimi-San Is Watching” (2017–2019), and Naoi’s Yuri Espoir (2019–), all of whom eagerly interpret any kind of affection between women as implying possible yuri relationships (Morishima 135–47; Kinosaki, vols. 1 and 2; Naoi). In Morishima’s “Honey and Mustard,” one character dismisses the idea that a woman might be in a romantic relationship with her female coworker on the grounds that “that one doesn’t believe in yuri,” implying that she is consequently blind to the romantic potential of their daily interactions (Morishima 43). Even in more recent yuri manga, in which characters are more likely to explicitly ask one another out and refer to each other as “girlfriends” rather than maintaining the ambiguities of traditional S relationships, there is no automatic assumption that a relationship between a dating couple is necessarily more serious or authentic than one “merely” based on akogare.

At the end of the long-running yuri manga Kiss and White Lily For My Dearest Girl (2013–19), the heroine asks each of her female high school friends how they define their relationships with the girls they are closest to. Some reply, “She’s my friend,” and some reply, “She’s my girlfriend,” but all are treated by the narrative as equally valid yuri couples (Canno, vol. 10). The plots of many yuri series, such as My Cute Little Kitten (2017–) or I Married My Best Friend to Shut My Parents Up (2018), are built on the idea that the boundary between female friendship and queer romance might be intensely permeable, with homoeroticism understood as an intensification of existing homosocial relations rather than an alternative to them. As a result, most yuri protagonists never formally ‘come out’ or define themselves as lesbians, even in stories about cohabiting adults who show every sign of intending to spend the rest of their lives together (Friedman, By Your Side 93; Altmann 13). As Friedman notes, in most yuri stories, “I love you” replaces “I am gay”; what their heroines discover and declare is their love for each other, rather than their orientation towards an entire gender (Friedman, By Your Side 95).

‘Coming out’ is also frequently rendered unnecessary by the fact that much yuri fiction take place in all-female settings where same-sex desire is normalised and heterosexuality is impossible: a tendency satirised by the yuri series The Whole of Humanity Has Gone Yuri Except For Me (2018–2020), in which a girl wakes up to find herself in a world inhabited entirely by women. Sometimes this lack of men is because the story is set within an all-female institution, such as a girls’ boarding school or a women’s college: the yuri franchise Kindred Spirits on the Roof (2012–15), which takes place in one such school, describes its setting as a ‘yuritopia’ (Hachi). This focus on all-female institutions frequently extends even to fantastical yuri narratives, such as A Witch’s Love at the End of the World (2018–2020) or Kiss the Scars of the Girls (2021–2023), which are set at all-girls schools for witches and vampires, respectively.

Often male characters remain absent from yuri even when the story moves outside such settings: mothers and sisters may appear when characters return home, for example, but fathers and brothers do not. The Dynasty Reader website marks such stories with the humorous tag “404: Men Not Found.” The story “Let’s Make a Yuri Manga!” includes a joke on this: when a mangaka suggests writing a yuri romance about a cross-dressing girl attending an all-boys school to seduce the (female) school doctor, her editor replies that “with this setting, people won’t even read as far as the reveal” because “they’ll tear it out and throw it away at the first page!” implying that no reader of yuri would ever tolerate reading about a majority-male setting (Hirao 249–50). In other yuri manga, such as I Don’t Need a Happy Ending (2023) or My Girlfriend’s Not Here Today (2021–), men are drawn without eyes or without faces to emphasise their status as non-characters, irrelevant to the world of female homosociality that constitutes the genre’s subject matter (Mikanuji; Iwami, vol. 1). A darker version of this trope appears in Yuri Espoir: whenever the protagonist sees the man she is meant to marry, he is drawn with his face scribbled out, suggesting his status as an embodiment of the looming world of compulsory heterosexuality that she, like most yuri fiction, is desperately trying to avoid looking at (Naoi). As long as their protagonists remain within such mono-gendered settings, homosexuality never needs to be declared because heterosexuality is never an option in the first place.

Finally, the influence of the Class S tradition lives on in the predominance of femme aesthetics in yuri media. Robertson notes that S relationships were traditionally juxtaposed with so-called ome relationships involving butch-femme pairings: the latter were more heavily stigmatised, as they were seen as implying physical sexual intimacy rather than the “pure” spiritual bonds associated with Class S (Robertson 68–69; see also Shamoon 37; Pflugfelder 163). Even today, yuri pairings are usually hyperbolically feminine, involving relationships between beautiful, slender, long-haired girls who dress in clothing such as sailor fuku and yukata. Gender nonconformity is rare, and the closest most yuri stories come to a butch aesthetic is the stock figure of the girls’ school “prince”: a tall, short-haired, athletic girl who enacts a model of “feminine masculinity” similar to the otokoyaku (female actors who play male roles) of the Takarazuka Revue, and who, like them, consequently finds themselves adored by women (Robertson 70–71, 146-7; Friedman, By Your Side 62–68).

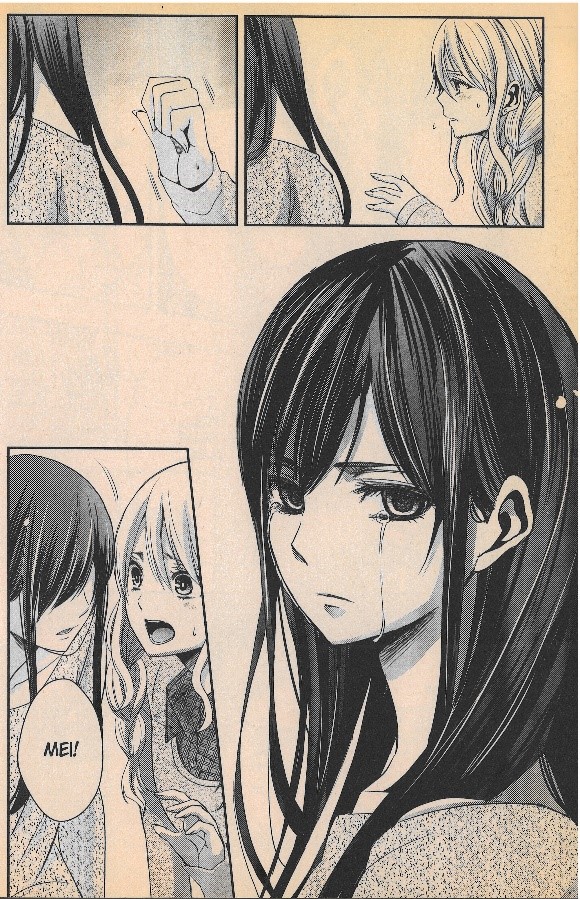

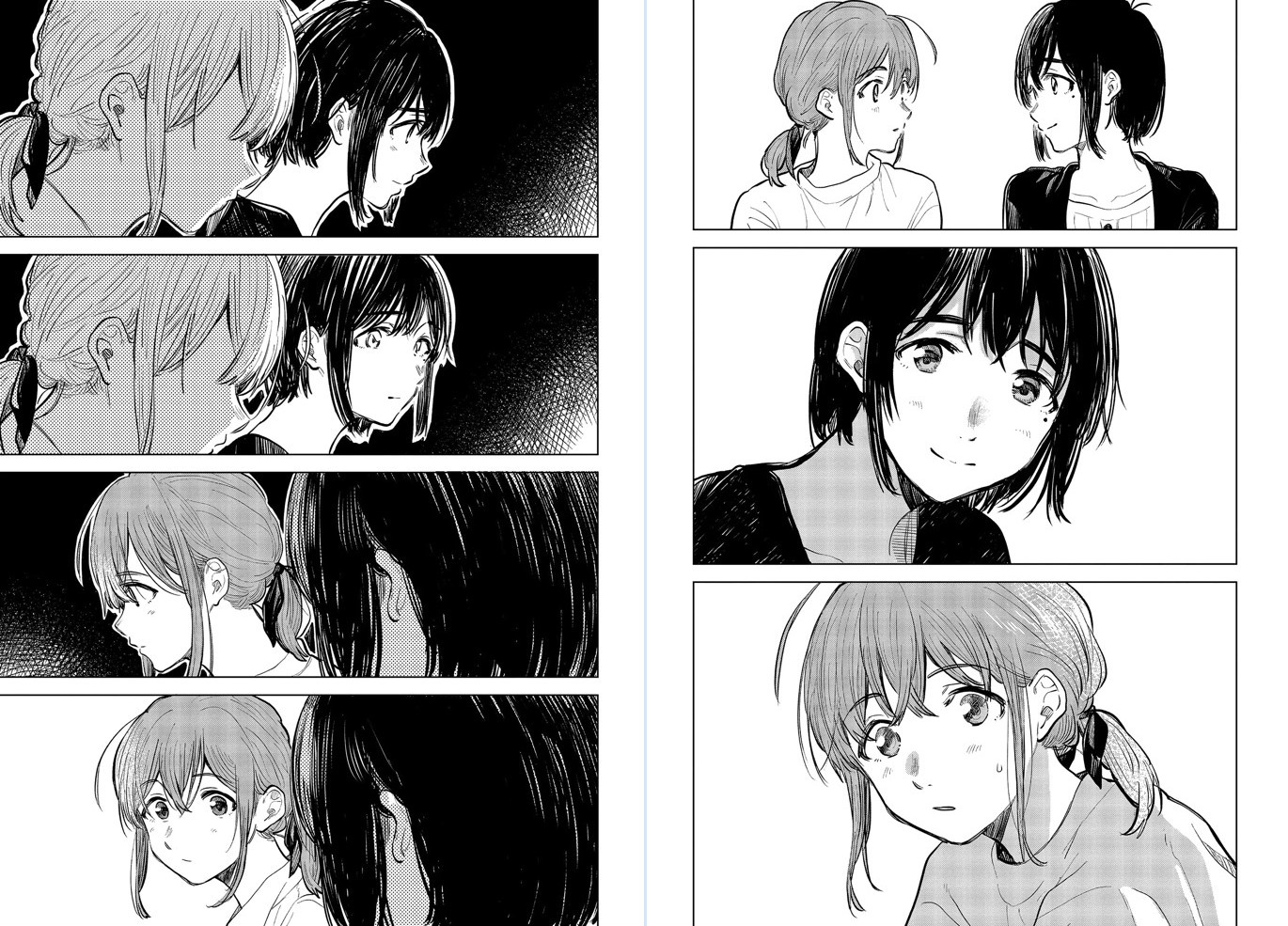

These aesthetics are visible in the distinctive visual style that yuri manga, as a genre, has developed since the 1990s. (See figure 1.) Detail is lavished on the clothes and hair of girls, and on the often-elaborate designs of their school uniforms. Close-up images of faces and hands are commonplace, and characters are drawn with huge eyes to better express their emotions. Backgrounds are usually simple and sometimes filled with nondiegetic elements such as darkness, flowers, or sparkles to communicate the feelings of the characters. The genre’s emphasis on yearning is communicated through its use of panelling: often multiple panels will pass wordlessly as one character gazes at another, gripped by emotions that they feel but cannot articulate. Splash pages are frequently used for key moments of joy or despair.

It is important to emphasise that not all yuri manga fits these descriptions. In recent years, especially following the international success of Nagata Kabi’s autobiographical manga My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness (2016, translation 2017), an increasing number of yuri titles have appeared depicting relationships between older characters inhabiting a mixed-gender adult world remote from the all-girl “yuritopias” of traditional yuri fiction. How Do We Relationship? (2018–), for example, tells the story of two lesbian students at a mixed university, while Even Though We’re Adults (2019–2023) tells the story of a woman in her thirties trying to navigate her relationship with another woman while also being married to a man. Such ‘shakaijin yuri’ (‘member of society yuri’) is much more likely to include characters who self-identify as lesbians, engage in explicitly sexual relationships, experience homophobia, and struggle to reconcile their desires with heteronormative social expectations; they also tend to be much less idealistic in their depictions of love between women. However, the genre’s centre of gravity still rests within the domain of ambiguous love–friendship relationships between schoolgirls, and, as Fugate notes, its progress towards greater realism is by no means uniform (45–52). Even series such as Yuri Is My Job! or Yuri Espoir, both of which build their narratives around the gap between the idealised fantasies of traditional yuri and the messier realities of teenage life, still make heavy use of yuri conventions, depicting worlds in which same-sex attraction between girls is commonplace and men are rare and often-unwelcome visitors. As I discuss below, it is precisely the genre’s ongoing commitment to such tropes that has proven so controversial with its Anglophone fandom.

“Yuri Bait”: Anglophone Frustrations with Yuri Narratives

Friedman has described how Western yuri fandom developed in relative isolation from Japanese yuri culture, meaning that Western readers often encountered such works without prior knowledge of the traditions that gave rise to them (Friedman, By Your Side 178). As both Valens and Fanasca note, translated yuri manga in the West is often marketed under the heading of “LGBT fiction,” and many Anglophone readers consequently approach it with expectations regarding queer representation that are in tension with the conventions of yuri as a genre (Valens; Fanasca, “Perspectives” 154). Modern Western LGBT fiction is generally understood as being inherently political, whereas yuri is an almost totally depoliticised genre in which love between women is usually depicted as a private matter that does not constitute any kind of challenge to the political status quo; as a result, as Maser notes, it has historically had an extremely ambivalent relationship with Japan’s actual lesbian community (Maser, “Beautiful” 153–56). Friedman has repeatedly described yuri as “lesbian content without lesbian identity” (By Your Side 20, 96, 200), and this absence has often been seen as a failing by audiences who want to see “queer characters be more openly queer” and who consequently critique the genre’s lack of explicit engagement with gay rights politics (Friedman, By Your Side 225; see also Maser, “Beautiful” 159; Altmann 27).

The seeds of this mismatch can be seen in Friedman’s 2009 interview with the yuri mangaka Morishima Akiko. In this interview, Morishima expressed her surprise that yuri had been able to acquire an audience outside Japan:

I would think that Yuri Manga is something that is strongly Japanese, a particular cultural convention of Japan. So, I am very glad and interested that overseas fans understand it. The word “Yuri” has reached people from far away countries, hasn’t it? Please continue your support and consideration of Japanese Yuri. (Morishima, Interview)

Morishima here clearly understands yuri to be a genre that is only intelligible within a specific Japanese cultural context. “Overseas fans” might “support” it, but they must necessarily engage with it as something inherently foreign, as “Japanese Yuri” (my italics). However, an anonymous commentator to Friedman’s website objected to Morishima’s statement that “Yuri Manga is something that is strongly Japanese,” posting a string of question marks before writing:

Did Morishima mean strongly Japanese in the sense that manga as a type of comics is strongly Japanese, or something else? Please tell me she didn’t mean lesbian romance stories are strongly Japanese—lesbians are everywhere instead of being more Japanese than the rest of us are, right? (Anonymous)

This comment implies that this commentator understood the word yuri to simply mean lesbian and accordingly took issue with Morishima’s description of it as being culturally specific to Japan—thus demonstrating that Morishima may have been overly optimistic in saying that “overseas fans understand [yuri].” Even now, Anglophone audiences frequently treat the word yuri as though it is (or should be) synonymous with ‘lesbian’, and express disappointment when this proves not to be the case.

Browsing Anglophone yuri fandom spaces, a stock set of complaints repeatedly resurface. Readers object to the lack of explicit coming out narratives or queer identity politics, as well as to the fact that most yuri stories never actually use the word ‘lesbian’ (VulcanTheForge). They are concerned by the genre’s focus on teenagers, worrying that such narratives reinforce harmful stereotypes about homosexuality being “just a phase” (Altmann 32). They express confusion at girls’ school settings in which it seems to be taken for granted that every student is attracted to other girls—what one reader describes as “those yuri manga where everyone is a lesbian and nobody questions it” (DrJamesFox, 25 Aug. 2024)—and sometimes argue that homosexuality loses its meaning as a distinct minority identity when heterosexuality is never even mentioned (KylieLemora; 5p1k4). Finally, and most frequently, they express disapproval of stories in which no explicit confirmation is ever given that the protagonists are more than “just friends.” For such readers, a confession of romantic love, a kiss, or a sex scene are seen as valid ways for a yuri story to resolve, but simple affirmations of affection (suki) or admiration (akogare) are not.

A decade ago, when yuri manga started to be regularly translated into English, Takashima noted that Anglophone yuri audiences had different preferences to their Japanese equivalents:

I doubt many young readers here go into it looking for the same focus on platonic relationships as Japanese yuri fans. Rather, more explicit works about cute girls making out with each other are driving the popularity of the genre abroad. . . . In a society that highly values diversity, stories that relegate their characters’ lesbian relationships to the realm of subtext may be viewed as exclusionary and discriminatory. (Takashima)

What Takashima correctly predicted here was the disapproval that many Anglophone readers have expressed towards yuri works in which the nature of the relationship between the main characters is left ambiguous or unstated, leading to frequent requests with titles like “Recommendation needed: media with absolutely NO ambiguity” (Thainen). Faced with yuri series whose protagonists never explicitly transition from “mere” friendship to a formal romantic and/or sexual relationship, such readers often express feelings of having been tricked or deceived. As mentioned above, the r/yuri_manga and r/yurimemes communities refer to such narratives as “yuri bait,” thus drawing an analogy with the often-made accusation that TV shows such as Supernatural (2005–2020) engage in “queerbaiting” by implying queer love between their male leads without ever explicitly confirming it on-screen (Woods and Hardman 584).

As I have discussed, this distinction is less meaningful when measured against the norms of traditional Japanese yuri media: a fact clearly illustrated by yuri anthologies such as Éclair (2016–2020), in which stories about middle-school girls making friends with their classmates sit alongside stories about sexual relationships between adult women, all of which are presented as equally valid manifestations of yuri love. The question “are they friends or are they girlfriends?” simply does not apply to a yuri series such as Futaribeya (2015–2023): its heroines share a yuri relationship characterised by mutual affection (they are inseparable) and physical intimacy (they share a bed), but not necessarily by dating or mutual sexual attraction. Anglophone audiences, however, often express impatience with such stories unless their protagonists can be placed within another taxonomised category of queer identity, such as “aroace” or “asexual” (NishikigiTakina).

The same difficulty with ambiguity extends to the authorship of yuri manga. In Japan most manga is published pseudonymously, and the public personae of mangaka is subject to strict editorial control, with the result that it is often unclear whether the author of a given work of yuri manga is male or female, straight or gay. However, these norms run counter to contemporary left-liberal Anglophone views that stories about minority experiences should explicitly be written by authors who have shared those experiences and can thus write about them from a position of authenticity—a position most famously articulated by the #ownvoices campaign of 2015–2021. Both Valens and Friedman, for example, have written on the importance of manga about queer women being written by queer women. As Friedman writes, “If this story is ours, we argue, then we should be involved” (Friedman, “Your Story”).

The Anglophone yuri fandom consequently invests considerable effort, and attributes considerable significance, to identifying the genders of yuri authors, giving rise to community projects such as the 2024 Yuri Mangaka Database, which contains information on the gender of 265 yuri mangaka. Where possible this database also includes information on the sexualities of these creators, although entries such as “probably not straight” or “seemed to suggest it without clarifying” bear witness to the gap between Japanese traditions of anonymity and Anglophone expectations of clear and explicit statements of identity (Maser, “Beautiful” 154). The knowledge that a given yuri work is by a woman—preferably a queer woman—is treated in such spaces as an important defence against accusations of “male gaze” fetishism. As one user writes, “In a perfect world I’d never read any GL [girls’ love manga] made by a man” (Azure-April).

These concerns coalesce particularly around yuri stories that remain close to the genre’s Class S origins, with same-sex love between girls presented as a normal part of adolescent female friendship rather than as a defiant expression of queer minority identity. Many boil down to a debate over whether ‘S relationships’ should be understood as a valid form of homosociality in their own terms or as a mere distortion of “true” lesbian sexuality: as Altmann notes, “For assimilationist readers, Class S influence and presence is an archaic limitation that ought to be rejected” (Altmann 32). Thus, Hanson, for example, argues that stories about traditional akogare relationships are actively harmful, “serving the purpose of explaining away same-sex attraction in a way that will push women towards the path to fulfilling society’s expectations,” and looks forward to their replacement by yuri works that “address lesbian identity.” Friedman, meanwhile, implies that Class S stories appeal primarily to straight readers, writing, “Straight fandom was happy enough with another schoolgirl story, but queer fandom was already asking where were the adults? Where were the lesbians? Where were the queer people in these queer stories?” (Friedman, “Your Story”). As one reader complains,

A lot of yuri, despite the premise of the genre, don’t like actually depicting the characters involved are [sic] gay. Sometimes it’s two straight girls employing a “if it’s with you it’s okay” exception, sometimes it’s the Class S bullshit that treats gayness in women as some fun experimental game for high schoolers they will ultimately end up “outgrowing”, sometimes tbe [sic] queerness is kept as vague and subtextual as possible to allow the straight men reading it to be able to imagine “joining in”. (asdfmovienerd39)

A sense of the complexities involved here can be gained from Valens, who writes,

That’s not to say that Western yuri fans should tell Japanese creators how to create yuri. That would be extremely inappropriate; we are, after all, a different culture approaching Japanese works from a different cultural lens. But it does mean that yuri doesn’t have to be a genre that just focuses on the male gaze. Yuri can also fall into the realm of queer literature, created by and for queer women. Yuri can capture our lives, our struggles, and our relationships with other women beyond mere fantasy.

Valens here articulates both a sense of yuri as a Japanese genre with its own culturally specific norms, and a sense that it would be desirable for it to conform with the norms of Western “queer literature”—to be “created by and for queer women” and to avoid “mere fantasy” and “the male gaze.” Given that Japanese mangaka seldom publicise their sexualities, and the fact that both self-consciously unrealistic Class S fantasy yuri like Maria Watches Over Us and sexually explicit “male gaze” yuri like Netsuzou Trap (2014–17) are frequently created by women, such aspirations are clearly in tension with the existing conventions of Japanese yuri. The insistence that yuri manga should be “for queer women” is even harder to fulfil, as Japanese yuri magazines are marketed interchangeably to male and female audiences. Between 2007 and 2010 Comic Yuri Hime published a separate magazine, Comic Yuri Hime S, aimed at male readers, reserving the main Comic Yuri Hime title for stories aimed at women. They soon found, however, that there was so much audience crossover between the two titles that it made more sense to fold both back into a single magazine (Dahlberg-Dodd 358, 365).

Collectively, these concerns demonstrate an ongoing pattern of tensions between what Japanese yuri media is and has been, and what many of its Anglophone readers would clearly prefer it to be. To illustrate these tensions further, I shall take as a case study the reception history of a specific work of yuri fiction: A Tropical Fish Yearns for Snow by Hagino Makoto.

“Between romance and friendship”: A Tropical Fish Yearns for Snow

A Tropical Fish Yearns for Snow was originally published in serialised manga form in Dengeki Maoh magazine from 2017 to 2021, and subsequently translated and released in English from 2019 to 2022. It tells the story of Amano and Honami, two girls who meet through their shared participation in their school’s aquarium club. (Aquariums have had a special place in yuri culture ever since 1996, when the foundational yuri couple Haruka and Michiru had an aquarium date in season 5 of Sailor Moon.) When its first chapters were uploaded to the Dynasty Scans website in 2018 with the tag “Subtext,” its readers expressed incredulity that it could be read as anything other than a lesbian romance:

YourShoes: That’s subtext . . . but it’s bold and italicized . . . and a bigger font than the actual text. (ellipses in original)

whitenight2013: It says subtext, but I think it’ll go all the way

FriedBreadfast: . . . yeah, i’d barely count this as subtext haha

Bowser Wowser: How the hell is this subtext this is gay as fuck

Structurally, A Tropical Fish Yearns for Snow is clearly a romance, and follows the basic meeting-barrier-attraction-declaration-parting-recognition-betrothal plot structure laid out by Pamela Regis (31–38). Its visual language is very much that of romance manga, full of lingering looks, shy handholding, blushes, smiles, and tearful embraces between its leads. (See figure 2.) Many of the statements they make certainly sound romantic: “No matter what you say . . . I want to listen to you . . . and get to know you . . . and touch you” (Hagino, vol. 7, ch. 26), for example, or “From now on, we will write our own happy ending for our own story” (vol. 9, ch. 32). The last line of the series is “In the vast sea, I found you,” placed as a caption beside their faces as Amano and Honami look at each other and smile, and the final, wordless image shows them holding hands, smiling delightedly at each other beneath a sky full of shooting stars (Hagino, vol. 9, epilogue). But they never formally date each other, never kiss, and never sleep together, and the question of whether they are friends or girlfriends is never even asked, let alone answered.

As a result, the initially positive response of many Anglophone readers turned to anger and disappointment as the story reached its end:

motormind: Frustration levels are over 9,000. The way the story ends makes absolutely no sense considering the emotional roller coaster that was presented up to that point.

Chris2aDegree: I’m still upset that they didn’t make them official to this day.

protectmomo: What a feeling of utter betrayal.

Predictably, the r/yuri_manga community labelled the series as a prime example of “yuri bait” and strongly expressed their feelings of betrayal:

mares8: If author doesn’t wanna draw yuri they should know difference between romance and friendship, but i think bait was on purpose else it would have lost readers

dankk175: Yea idk how tf the author expect [sic] ppl to interpret the girl as “friends” after drawing the most gay shit possible. One of the manga that i truly feel like a waste of time

SadDoctor: Chapter after chapter is like going riiiight to the edge of not saying it’s gay, but doing everything but. The story doesn’t even make sense if it’s not romantic.

halbeshendel: So here’s the thing. It’s super gay. The only person who doesn’t realize they’re gay are the girls and the author. Just think of it like “these girls are gay and they’ll figure it out in college.”

These objections are clearly born out of longstanding concerns over lesbian erasure in media. Thus ‘Rotang-Klan’ complains that “They look longingly at each other very gayly after having the most gay interaction possible and basically say ‘we’re gal pals,’” an allusion to the internet meme “just gals being pals,” which refers to the tendency of commentators to dismiss lesbian relationships in both media and reality as “just friendship” unless and until they are explicitly shown to be romantic in nature (“Gal Pals”). The implication, in this comment and many others, is that Hagino must in some sense be aware that her protagonists are “really” lesbians, but has chosen to conceal this fact due to editorial pressure and/or homophobia.

However, many of the arguments presented in these threads also hinge on the assumption that the distinction between friendship and romance is (or should be) unambiguous and that authors “should know [the] difference between romance and friendship.” “If im [sic] writing about some stupid platonic friendship, I won’t let them blush and keep getting dizzy, because they find the other one that beautiful and nice. . .” writes ‘Puzzleheaded_Gap_19’. “[T]hat is creepy as fuck, if you look at it at that way. . . . I’m sure my best friend would think I’m a perv and a creep, behaving pike [sic] that to her, while telling her ‘ignore the staring, blushing, stalking, touching, non stop writing and anything else, because my love for you is that fucking platonic!’” (Puzzleheaded_Gap_19, 24 Apr. 2022). Such comments imply a preference for a strict separation between homosocial friendship and homosexual romance, with behaviours that would be acceptable in the latter context—staring, blushing, touching—becoming “creepy as fuck” in the former, the actions of “a perv and a creep.” Within this paradigm, keeping Amano and Honami’s relationship ambiguous becomes not just frustrating but morally objectionable, and if they wish to keep behaving in ways that are “the most gay shit possible” and “gay as fuck,” then it is incumbent upon them to clarify the nature of their relationship as quickly as possible.

These attitudes are easily understood within the context of a fandom hungry for explicit queer representation and frustrated by media ‘queerbaiting’, which is seen as confusing and exploitative for queer audiences (Woods and Hardman 589). In older yuri-adjacent works such as Noir (2001), lesbian relationships often genuinely did remain unspoken, forcing fans to deduce the nature of the relationship between its heroines from nonverbal cues and the fact they only seemed to own one bed between them. Now that direct depictions of queer relationships are less taboo in Japanese media, there is understandable resentment of creators who seem insistent on maintaining plausible deniability even in contexts where it is no longer required. These preferences also clearly bespeak a desire for the validation of adolescent same-sex love as not just a transitory phase or ambiguous teenage crush, but as the starting point of a lifelong queer identity—thus the hope of ‘halbeshendel’ that Amano and Honami will “figure it [i.e. their lesbian sexuality] out in college.” From this perspective, Hagino’s decision to write about “passionate friendship” instead of explicit lesbian desire can only be read as a failure to properly carry out her role as a creator of “real” yuri manga. As Reddit user ‘DrJamesFox’ writes,

[T]oo often it feels like more subtext-oriented works keep themselves from going full romance because of self or actual censorship against homosexuality. Such censorship stems from beliefs such as these relationships being “a phase to be grown out of” or even that they’re “not proper”. That such entertainment media shouldn’t go beyond subtext because these relationships only have value as entertainment and should be avoided being shown in full so as not to “encourage” such behavior.

I’ve begun to feel that accepting such a half-hearted attitude towards gay relationships in media is the same as endorsing such an attitude as acceptable in real life. (2 Sept. 2024)

Such objections are clearly driven by a laudable desire to champion queer representation in media. However, the perspective implied here, in which “gay shit” becomes permissible only within the confines of an explicitly declared queer relationship, risks seeming oddly repressive when compared to the tapestry of homosocial intimacies depicted by many yuri works. As Joseph Brennan notes in his discussion of slash fiction, insisting on a strict “homosocial/homosexual binary” means “ignor[ing] the grey area between the terms where eroticism resides” (Brennan 195).

In her discussion of yuri, Nagaike invokes Adrienne Rich’s concept of the lesbian continuum, within which “lesbianism should not be narrowly defined merely as a single sexual orientation, but rather viewed as part of a female-oriented continuum that reflects women’s psychological experiences in bonding with other women” (Nagaike). By insisting on a clear division between “romance” and “friendship,” with “gay shit” permitted only on one side of it, these readings imply that only the extreme end of such a continuum can or should be legitimated as “real” queer love. In so doing, they risk replicating the patronising cultural patterns, noted by Kawasaka Kazuyoshi, in which white Westerners are positioned as the bearers of “true” or “authentic” understanding of queer sexuality, of which indigenous Japanese modes can only ever be understood as imperfect approximations (Kawasaka 31–32). As Welker notes, “rather than being some form of intercultural communication,” such attitudes can easily lapse into “a stance where the west is advanced and Japan is still developing in terms of its homosexual communities” (Inoue).

The issues raised here are not just transcultural but transhistorical. As scholars such as Sharon Marcus and Martha Vicinus have pointed out, “passionate friendship” between girls was once a normalised aspect of female adolescence in Europe and America as well; indeed, Japanese S relationships, like the schools in which they took place, were originally modelled heavily on their Western counterparts (Marcus chapter 1, Vicinus passim, see also Sahli passim; Pflugfelder 133; Welker, Transfiguring 69). Scholars of nineteenth-century literature have long noted the intense physical and emotional intimacy of female friendships in novels such as Mansfield Park (1814), Jane Eyre (1847), and Bleak House (1853)— friendships that, like yuri relationships, were often characterised by shared beds, touches, kisses, and mutual declarations of love (Nestor 44–5). As in Japan, these trends reached their most highly developed forms in the girls’ schools of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, giving rise to emotionally charged homosocial cultures in which, as Vicinus writes, “even the most trivial act of homage—helping the loved one put on her coat or cleaning the blackboard—could gain emotional significance through later conversations with other girls” (217; see also Beccalossi 73–75, 199–201). (The parallels here with the emphasis placed on minor but emotionally charged interactions between girls in yuri manga is obvious.) It is no coincidence that mass-market romance fiction arose during the same decades that saw such relationships increasingly stigmatised as “homosexual”: the traditional Anglophone romance novel constituted a kind of mythology of heterosexuality, which aimed to assert, contrary to most prior historical experience, that women might plausibly find in their heterosexual relationships with men the same kind of emotional fulfilment that they had previously looked for chiefly in their relationships with other women (Vicinus 228). Much of the edifice of modern romance culture was thus built on the ruins of prior modes of female homosociality.

In the early 1990s, Gregory Pflugfelder interviewed several Japanese women about their memories of S relationships as schoolgirls in the 1920s. Describing his findings, he writes,

What seemed to have most lingered in their minds after more than a half-century was a sense of youthful enthusiasm and of emotional richness. I was often struck by the candor, sometimes the perceptible pleasure, with which these women, who had married after graduation and now had children and grandchildren, shared their personal recollections of “S”—a phenomenon that sexologists and others had begun to stigmatize as “same-sex love” even in their own time. This gap in perceptions serves as a useful reminder that adult authorities possessed only a limited power to shape the experiences, and the subsequent memories, of schoolgirls, and that the discourses of outsiders can never fully capture the meanings that “S” held for its participants. (Pflugfelder 175)

It may indeed be impossible, at this distance in time, to fully reconstruct the emotional world of prewar ‘S relationship’ culture, of which modern yuri media can only ever be an imperfect reflection, but it is precisely this sense of the “emotional richness” of the “memories of schoolgirls” that yuri manga excels in communicating. Being made up of still images, its narratives are built around snapshot moments of tremendous emotional intensity: the moment one girl turns and sees her classmate throwing flowers to her out of a window, or nestles against her for warmth in a darkened classroom, or reaches for her hand at a summer festival just as the fireworks start. The visual vocabulary of yuri, with its extreme close-ups, huge eyes, swirling skirts, blooming lilies, and blowing hair, constitutes a set of tools for communicating the emotional force of these moments and hence transmitting to its readers some intimation of “the meanings that ‘S’ held for its participants.” (See figure 3.)

Unlike the linear teleology implied by traditional ‘coming out’ narratives, these texts do not always offer any guarantee that their protagonists will ultimately identify as ‘lesbians’—but regardless of what futures await them, yuri narratives make clear that their heroines will remain indelibly marked and changed by these moments of intense emotional connection. It is hard to imagine most heterosexual marriages being able to compete with the emotional power of the average yuri romance; as Vicinus notes in her study of “passionate friendships,” “Many women . . . appear to have found a more complete love as an adolescent than they were ever to find with a man” (219). Some yuri stories even build specifically towards a promise to remember, just as Pflugfelder’s interviewees still vividly remembered their own long-gone ‘S relationships’ even after lifetimes spent as wives and mothers within an oppressively heteronormative society. Parting from her beloved female friend to advance towards an uncertain (and very possibly heterosexual) future, the heroine of Yuikawa’s “To a Nameless Flower” weeps and insists that “I won’t forget,” promising to carry the memory of their private language of flowers, and the relationship it stands for, forward through the rest of her life:

Twisting flower. Firework grass.

Wheat grass. Star candy.

I don’t know the real names of these wild plants.

But no-one else knows . . .

. . . our special names for these flowers. (Yuikawa 30-2)

Definitions of romance are notoriously fraught, and there are clearly many readers for whom works such as A Tropical Fish Yearns for Snow do not fulfil them. Just as Takashima predicted, Anglophone audiences have proven most comfortable with yuri manga in which women overtly affirm their status as one another’s lovers or girlfriends, in accordance with the genre norms of the Western young adult lesbian romance fiction that most yuri superficially resembles. As I have discussed, yuri is also a deeply depoliticised genre, and readers who look to it for works “created by and for queer women” or defiant articulations of queer identity are likely to be frequently disappointed. But as Nagaike’s invocation of Rich’s lesbian continuum suggests, the continuing celebration of passionate friendships between women in yuri media does not have to be understood only in negative terms, as “real” lesbian romances too encumbered by homophobic patriarchal holdovers to make it to the finish line. More optimistically, such narratives can also be read as part of a wider lesbian tradition that is less invested in fixed categories of identity, bringing out the romantic queer potential of a range of homosocial relationships that might not otherwise be understood in such terms. By so doing, the translation of yuri romance manga into English provides Anglophone readers with a glimpse into earlier and other modes of understanding and celebrating same-sex love between women—modes in which our own culture was once equally rich, and which queer critics such as Heather Love have warned us to not be too hasty in forgetting (30).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Sophia Crawford and Professor Jana Funke for their generous insights and feedback on previous drafts of this article.

A Note on Names

All Japanese names have been given in Japanese style, with family name preceding given name.

[1] Also transliterated as ‘resubian’, especially in older texts.

Works Cited

Primary Sources: Yuri Manga in English

Canno. Kiss and White Lily for My Dearest Girl. Translated by Jocelyne Allen, Yen Press, 2017–2019. 10 vols.

Ito, Hachi. Kindred Spirits on the Roof. Translated by Amy Osteraas, adapted by David Liederman, Seven Seas, 2015.

Hagino, Makoto. A Tropical Fish Yearns for Snow. Translated by John Werry, Viz Media, 2019–2022. 9 vols.

Hirao, Auri. “Let’s Make a Yuri Manga!” Éclair Bleue, translated by Eleanor Summers, Yen Press, 2020, pp. 249–52.

Ikeda, Takashi. Whispered Words. Translated by Julianne Neville. One Peace Books, 2014. 3 vols.

Iwami, Kiyoko. My Girlfriend’s Not Here Today. Translated by Avery Hutley, Seven Seas, 2024. 2 vols.

Kinosaki, Kazura. Strawberry Fields Once Again. Translated by Amanda Haley, Yen Press, 2020–2021. 3 vols.

Mikanuji. I Don’t Need a Happy Ending. Translated by Emma Schumacker, Yen Press, 2023.

Morishima, Akiko. The Conditions of Paradise: Azure Dreams. Translated by Elina Ishikawa, adapted by Asha Bardon, Seven Seas, 2021.

Naoi, Mai. Yuri Espoir. Translated by Caroline Wong, Tokyopop, 2022–2024. 4 vols.

Nawoko, Voiceful. Translated by Satsuki Yamashita, adapted by Patrick Seitz, Seven Seas, 2007.

Saburouta, Citrus. Translated by Catherine Ross, adapted by Shannon Fay, Seven Seas, 2014 –2019. 10 vols.

Shinonome, Mizuo. First Love Sisters. Translated by Beni Axia Conrad, adapted by Lorelei Laird, Seven Seas, 2007.

Yuikawa, Kazuno. “To a Nameless Flower.” Éclair Rouge, translated by Eleanor Summers, Yen Press, 2020, pp. 5–34.

Secondary Sources

5p1k4. “Men in yuri.” Reddit, 29 Jan. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/1aeesdm/men_in_yuri/.

Akaeda, Kanako. “Intimate Relationships between Women as Romantic Love in Modern Japan.” Conceptualizing Friendship in Time and Place, edited by Carla Risseeuw and Marlein van Raalte, Brill, 2017, pp. 184–204.

Altmann, Dale. “Cross-Cultural Reception in the Western Yuri Fandom: Assimilationist and Transcultural Readings.” 2017. University of Wollongong, MA thesis, https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2558&context=theses1.

Anonymous. Comment on Morishima Akiko interview with Erica Friedman. Okazu, 26 Oct. 2009, https://okazu.yuricon.com/2009/10/25/interview-with-yuri-manga-artist-morishima-akiko.

asdfmovienerd39. “Yuri that depicts the reality of being gay.” Reddit, 30 Aug. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/1f50l1k/yuri_that_depicts_the_reality_of_being_gay/.

Azure-April. Comment on memtoyuri’s thread “NEWS: Pito, creator of GL manhwa ‘Her Pet’ and ‘My Joy’ used revenge porn as reference.” Reddit, 1 Sept. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/1f6apqa/ news_pito_creator_of_gl_manhwa_her_pet_and_my_joy/.

Bauman, Nicki. “Yuri Is for Everyone.” Anime Feminist, 12 Feb. 2020, https://www.animefeminist.com/yuri-is-for-everyone-an-analysis-of-yuri-demographics-and-readership/.

Beccalossi, Chiara. Female Sexual Inversion: Same-Sex Desires in Italian and British Sexology, c.1870–1920. Palgrave, 2012.

Bowser Wowser. Comment on “Nettaigyo wa Yuki ni Kogareru discussion.” Dynasty Reader, 11 Apr. 2018, https://dynasty-scans.com/forum/topics/13728-nettaigyo-wa-yuki-ni-kogareru-discussion.

Brennan, Joseph. “Queerbaiting: The ‘Playful’ Possibilities of Homoeroticism.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 21, no. 2, 2018, pp. 189–206.

Chris2aDegree. Comment on “Nettaigyo wa Yuki ni Kogareru discussion.” Dynasty Reader, 17 Feb. 2024, https://dynasty-scans.com/forum/topics/13728-nettaigyo-wa-yuki-ni-kogareru-discussion.

Dahlberg-Dodd, Hannah. “Script Variation as Audience Design: Imagining Readership and Community in Japanese Yuri Comics.” Language in Society, vol. 49, no. 3, 2020, pp. 357–78.

dankk175. Comment on dcmaniac8’s thread “I got yuri baited by A Tropical Fish Yearns for Snow.” Reddit, 7 Jan. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/190ow7s/i_got_yuri_baited_by_a_tropical_fish_yearns_for/.

DotBig2348. “My perspective on yuribait.” Reddit, 21 Apr. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/1c9gxgj/my_perspective_on_yuribait/.

DrJamesFox. Comment on Guthrum06’s thread “Can a Visual Novel be Yuri if It Has No Romance?” Reddit, 2 Sept. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yurivisualnovels/comments/1f7jy4n/can_a_visual_novel_be_yuri_if_it_has_no_romance/.

———. Comment on KylieLemora’s thread “Yuri manga without any het.” Reddit, 25 Aug. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/1f12nkl/yuri_manga_without_any_het_even_mentions_if/.

Fanasca, Marta. “Perspectives on the Italian BL and Yuri Manga Market: Toward the Development of Local Voices.” Mechademia, vol. 13, no. 1, 2020, pp. 153–58.

———. “Tales of Lilies and Girls’ Love: The Depiction of Female/Female Relationships in Yuri Manga.” Tracing Pathways: Interdisciplinary Studies on Modern and Contemporary East Asia, edited by Diego Cucinelli and Andrea Scibetta, Firenze UP, 2020, pp. 51–66.

FriedBreadfast. Comment on “Nettaigyo wa Yuki ni Kogareru discussion.” Dynasty Reader, 11 Apr. 2018, https://dynasty-scans.com/forum/topics/13728-nettaigyo-wa-yuki-ni-kogareru-discussion.

Friedman, Erica. By Your Side: The First 100 Years of Yuri Anime and Manga. Journey, 2022.

———. “Your Story, Our Story, My Story: When and Why Queer Representation Misses the Mark.” Ozaku, 3 Jan. 2021, https://okazu.yuricon.com/2021/01/03/your-story-our-story-my-story-when-and-why-queer-representation-misses-the-mark/.

Fugate, Natalie. “Queer Subtext and Fanmade Text in Maria-sama ga miteru.” 2021. University of Illinois, MA thesis, https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/123157.

“Gal Pals.” Know Your Meme, 29 Jan. 2025, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/gal-pals.

halbeshendel. Comment on dcmaniac8’s thread “I got yuri baited by A Tropical Fish Yearns for Snow.” Reddit, 7 Jan. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/190ow7s/i_got_yuri_baited_by_a_tropical_fish_yearns_for/.

Hanson, Katherine. “The Evolution of ‘Recognition/Assertion of a Lesbian Identity’ vs ‘Akogare’ in Manga.” Yuricon, 2012, https://www.yuricon.com/oldessays/lesbian-identity-in-manga/.

Hernandez, Yaritza. “The Impact of Globalization on Yuri and Fan Activism.” Yuricon, 2009, https://www.yuricon.com/oldessays/globalization/.

Inoue, Meimy. “Celebrating Lesbian Sexuality: An Interview with Inoue Meimy, Editor of Japanese Lesbian Erotic Lifestyle Magazine Carmilla.” Interview with Katsuhiko Suganuma and James Welker. Intersections, no. 12, 2006, http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue12/welker2.html.

Kawasaka, Kazuyoshi. “The Progress of LGBT Rights in Japan in the 2010s.” Beyond Diversity Queer Politics, Activism, and Representation in Contemporary Japan, edited by Kazuyoshi Kawasaka and Stefan Würrer, De Gruyter, 2024, pp. 21–38.

Khor, Diana. “The Foreign Gaze? A Critical Look at Claims about Same-Sex Sexuality in Japan in the English Language Literature.” Gender and Sexuality, vol. 5, 2010, pp. 45–59.

KylieLemora. “Yuri manga without any het.” Reddit, 25 Aug. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/1f12nkl/yuri_manga_without_any_het_even_mentions_if/.

Love, Heather. Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. Harvard UP, 2007.

Marcus, Sharon. Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England. Princeton UP, 2009.

mares8. Comment on dcmaniac8’s thread “I got yuri baited by A Tropical Fish Yearns for Snow.” Reddit, 7 Jan. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/190ow7s/i_got_yuri_baited_by_a_tropical_fish_yearns_for/.

Maser, Verena. “Beautiful and Innocent: Female Same-Sex Intimacy in the Japanese Yuri Genre.” 2013. Trier University, PhD thesis, https://ubt.opus.hbz-nrw.de/opus45-ubtr/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/695/file/Maser_Beautiful_and_Innocent.pdf.

———. “Translated Yuri Manga in Germany.” Mechademia, vol. 13, no. 1, 2020, pp. 159–62.

McLelland, Mark. Queer Japan from the Pacific War to the Internet Age. Rowman and Littlefield, 2005.

Morishima, Akiko. Interview with Erica Friedman. Okazu, 25 Oct. 2009, https://okazu.yuricon.com/2009/10/25/interview-with-yuri-manga-artist-morishima-akiko/.

motormind. Comment on “Nettaigyo wa Yuki ni Kogareru discussion.” Dynasty Reader, 16 Feb. 2024, https://dynasty-scans.com/forum/topics/13728-nettaigyo-wa-yuki-ni-kogareru-discussion.

Nakamura, Karen. “The Chrysanthemum and the Queer: Ethnographic and Historical Perspectives on Sexuality in Japan.” Journal of Homosexuality, vol. 52, no. 3–4, 2007, pp. 267–81.

Nakaige, Kazumi. “The Sexual and Textual Politics of Japanese Lesbian Comics: Reading Romantic and Erotic Yuri Narratives.” Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 2010, https://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/articles/2010/Nagaike.html.

Nestor, Pauline. “Female Friendships in Mid-Victorian England: New Patterns and Possibilities.” Literature and History, vol. 17, no. 1, 2008, pp. 36–47.

NishikigiTakina. “Futaribeya: A Room For Two.” Reddit, 25 July 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/1ebsu8h/futaribeya_a_room_for_two.

Pflugfelder, Gregory. “S Is for Sister: Schoolgirl Intimacy and ‘Same-Sex Love’ in Early Twentieth-Century Japan.” Gendering Modern Japanese History, edited by Kathleen Uno, Harvard University Asia Centre, 2005, pp. 133–90.

protectmomo. Comment on “Nettaigyo wa Yuki ni Kogareru discussion.” Dynasty Reader, 18 Feb. 2024, https://dynasty-scans.com/forum/topics/13728-nettaigyo-wa-yuki-ni-kogareru-discussion.

Puzzleheaded_Gap_19. “A tropical fish yearns for snow is nothing but ridiculous.” Reddit, 23 Apr. 2022, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/uaips1/a_tropical_fish_yearns_for_snow_is_nothing_but/.

———. Comment on their thread “A tropical fish yearns for snow is nothing but ridiculous.” Reddit, 24 Apr. 2022, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/uaips1/a_tropical_fish_yearns_for_snow_is_nothing_but/.

Regis, Pamela. A Natural History of the Romance Novel. U of Pennsylvania P, 2003.

Robertson, Jennifer. Takarazuka: Sexual Politics and Popular Culture in Modern Japan. U of California P, 1998.

Rotang-Klan. Comment on Puzzleheaded_Gap_19’s thread “A tropical fish yearns for snow is nothing but ridiculous.” Reddit, 19 Sep. 2022, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/uaips1/a_tropical_fish_yearns_for_snow_is_nothing_but/.

SadDoctor. Comment on dcmaniac8’s thread “I got yuri baited by A Tropical Fish Yearns for Snow.” Reddit, 7 Jan. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/190ow7s/i_got_yuri_baited_by_a_tropical_fish_yearns_for/.

Sahli, Nancy. “Smashing: Women’s Relationships before the Fall.”’ History of Women in the United States, vol. 10, edited by Nancy Cott, K. G. Saur, 1993, pp. 286–305.

Shamoon, Deborah. Passionate Friendship: The Aesthetics of Girl’s Culture in Japan. U of Hawaii P, 2012.

Takashima, Rika. “Japan: Fertile Ground for the Cultivation of Yuri.” Yuricon, 2014, https://www.yuricon.com/oldessays/japan-fertile-ground-for-the-cultivation-of-yuri/.

Thainen. “Recommendation needed: media with absolutely NO ambiguity.” Reddit, 25 Aug. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/1f1f3j7/recommendation_needed_media_with_absoluely_no/

Valens, Ana. “Rethinking Yuri: How Lesbian Mangaka Return the Genre to Its Roots.” The Mary Sue, 6 Oct. 2016, https://www.themarysue.com/rethinking-yuri/.

Vicinus, Martha. “Distance and Desire: English Boarding School Friendships, 1870–1920.” Hidden From History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past, edited by Martin Duberman, et al., Penguin, 1989, pp. 212–29.

VulcanTheForge.”Yuri manga that actually use the L-word.” Reddit, 6 Aug. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/yuri_manga/comments/1elu5ws/yuri_manga_that_actually_use_the_lword/.

Welker, James. “Lilies of the Margin: Beautiful Boys and Queer Female Identities in Japan.” AsiapacifiQUEER: Rethinking Genders and Identities, edited by Fran Martin, et al., U of Illinois P, 2008, pp. 46–66.

———. “Telling Her Story: Narrating a Japanese Lesbian Community.” Journal of Lesbian Studies, vol. 14, no. 4, 2010, pp. 359–80.

———. “Toward a History of ‘Lesbian History’ in Japan.” Culture, Theory and Critique, vol. 58, 2017, pp. 147–65.

———. Transfiguring Women in Late Twentieth-Century Japan: Feminists, Lesbians, and Girls’ Comics Artists and Fans. U of Hawai’i P, 2024.

whitenight2013. Comment on “Nettaigyo wa Yuki ni Kogareru discussion.” Dynasty Reader, 11 Apr. 2018, https://dynasty-scans.com/forum/topics/13728-nettaigyo-wa-yuki-ni-kogareru-discussion.

Wood, Andrea. “Making the Invisible Visible: Lesbian Romance Comics for Women.” Feminist Studies, vol. 41, no. 2, 2015, pp. 293–334.

Woods, Nicole, and Doug Hardman. “‘It’s just absolutely everywhere’: Understanding LGBTQ Experiences of Queerbaiting.” Psychology and Sexuality, vol. 13, no. 4, 2022, pp. 583–94.

Yeung, Ka Yi. “Alternative Sexualities/Intimacies? Yuri Fans Community in the Chinese context.” 2017. Lingnan University, MA thesis, https://commons.ln.edu.hk/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044&context=soc_etd

YourShoes. Comment on “Nettaigyo wa Yuki ni Kogareru discussion.” Dynasty Reader, 10 Apr. 2018, https://dynasty-scans.com/forum/topics/13728-nettaigyo-wa-yuki-ni-kogareru-discussion.

“Yuri Mangaka Database 2.” Google Sheets, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vQqV7eWgqi-NL39QdMXTDrjX_FyCaNOAvCD50Ai0TUNwupOx1c2h58mbr4jkz0-qwO_e0uRgRltt5_J/pubhtml#.